Neither it was the cloudburst nor the avalanche but the “glacier surge” that buried the men stationed at Siachen, Arshad H Abbasi, an expert on water and climate changes, told The News.

“Glacier surge is phenomena caused either by rise in temperature or some tectonic movement, where a glacier advances substantially, moving at velocities up to 100 times faster than normal,” he said.

Keeping in view the record of tremors occurring in the last one month, Abbasi insists that rise in temperature caused “the increase of melt-water at the base of a glacier that untimely reduced the frictional restrictions to glacial ice flow and transfer of large volumes of ice on Pakistan’s Army Camp.”

“The rising temperature is directly proportional with huge number of military presence in area. That is fundamental cause of melting glacier at an unprecedented rate,” he argued. “The actual retreat is not only evident by the snout of the glacier, but the real concern is the reduction of the glacier’s mass balance, which is the difference between accumulation and ablation (melting and sublimation).”

Having received the latest images of the glacier, Abbasi says it shows “visible cracks in the midst of glacier and above all the number of glacial lakes that have formed.”

‘Voodoo Science’ practitioners are justified in saying that Indian Army is playing pivotal role in global warming, causing the fast melting of Siachen Glacier.

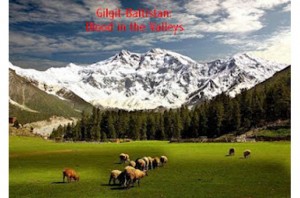

Those claiming Siachen is melting due to global warming are advised to look into the report titled ‘Advancing Glaciers and Positive Mass Anomaly in the Karakoram Himalaya’ published by NASA. The report says of the glaciers in Karakoram, more than 65 percent are growing. They term abnormality as “Karakoram anomaly”. Therefore, it’s just a myth that Siachen is melting because of global warming, as it’s case of direct human interference, climate change.

During Track-II dialogues, Abbasi said, he had again been raising the question of the audit of Siachen Glacier to know the reduction of its volume, which was always declined by the Indian government. The climate change is by far the biggest threat ever encountered by humankind.

“It is time that the global leadership and community work with Pakistani and Indian leaders to save Himalayan glaciers by solving the longstanding Siachen dispute. This conflict is adding to environmental degradation, sea level rise and changing climate pattern but it is also depriving the poor of both countries of close to one billion dollars every year that these countries spend to maintain troops there,” he said.