(Credit: alamy.com)

Growing tensions between India and Pakistan is persuading the Chinese establishment to focus on the Kashmir issue as an impediment to Beijing’s One Belt One Road (OBOR) initiative, with the China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) at its core.

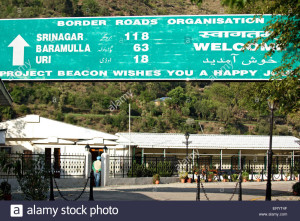

The Uri incident, which has escalated India’s efforts to garner international support to dock Pakistan as a sponsor of terrorism, after 18 Indian soldiers were killed in a cross-border raid, and Islamabad’s re-energised drive to internationalise Kashmir, has fueled considerable anxiety in Beijing. The Chinese Foreign Ministry has on two occasions since the Uri incident, called upon India and Pakistan to exercise restraint and resume their stalled dialogue.

Military tensions a threat

Apart from the nuclear dimension, which turns military tensions between India and Pakistan into a lurking threat to international peace and security, analysts say that the Chinese have a more pressing and immediate, concern — the fallout of Indo-Pak friction on the viability of the CPEC.

The CPEC links the Pakistani port of Gwadar with Kashgar in Xinjiang. It is part of China’s high-stake OBOR connectivity initiative in Eurasia, which would allow China to gate-crash as an indispensable rule-maker of international trade and commerce. Coupled with its aspiration to develop a string of ports and coastal economic hubs, along its maritime trading routes, China’s Maritime Silk Road (MSR), would also be central to Beijing’s rise as a mature global power.

China hopes to replicate its dramatic success in developing coastal hubs such as Shanghai and Shenzhen as models for developing new shore-based icons along the Indian Ocean coastline.

Passing through Baluchistan, PoK

Unsurprisingly, the CPEC, which passes through a section of Pakistan Occupied Kashmir (PoK), was apparently the primary focus of talks between Chinese Prime Minister Li Keqiang and his Pakistani counterpart, Nawaz Sharif at their meeting on the sidelines of the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA). A posting of the September 21 talks, on the Chinese Foreign Ministry website underscored that Prime Minister Li “pointed out that at present, bilateral practical cooperation, with China-Pakistan economic corridor as the priority, has achieved positive progress.”

Yet, Mr. Li did not hide Beijing’s security concerns, when he stressed, “It is hoped that Pakistan can reinforce prevention on the security risk of the projects and continue to provide safety protection to the programme construction and Chinese personnel in Pakistan.”

Bugti’s asylum

A large part of the CPEC passes through Baluchistan. India has raised Pakistan’s alleged human rights violations in the province at the international level — a policy shift that was underscored by New Delhi’s assertions on the Baluch issue, earlier this month, at the UN Human Rights Council in Geneva. New Delhi has also signaled its possible readiness to provide asylum to Baluchistan Republican Party (BRP) leader Brahamdagh Bugti.

The Hong Kong based South China Morning Post quoted Pakistan commentator Najam Sethi as saying that “Bugti’s asylum suggests that India will make Baluchistan a central plank of its strategy, politically and diplomatically.” He added: “China is beginning to worry about all these.”

‘Disaster for whole region’

India’s exertions in Baluchistan have not gone unnoticed in China. In an earlier interview with The Hindu, Chinese scholar Hu Shisheng highlighted that Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s reference to Baluchistan in his independence day address signaled “a watershed moment in India’s policy towards Pakistan in the future.” He added: “We cannot figure out what could be its result and consequences, but my personal hunch is that it could be disastrous for the whole region; for all the relations — especially between Pakistan and India, China and India, especially among the three countries. That is the real concern.”

He also pointed out the contrary to the perception that China was developing the CPEC to lower its commercial dependence on the Malacca straits, the prime strategic motivation behind the project was to ensure Pakistan’s economic stability. In turn, it was assumed this would help dry up terror sanctuaries in Pakistan, and prevent the outflow of militants, in the region, including China and Central Asia — all part of the expanding OBOR network.

It is in the K-word

Chinese academics have also begun to debate the regional fall-out of the Kashmir issue, and the benefits to the CPEC, in case a modus vivendi is achieved to address this thorny dispute. “If India and Pakistan can resolve the Kashmir problem, CPEC would not be an obstacle among China, India and Pakistan,” Professor Long Xingchun, Director of Center of India Studies, at China West Normal University, told The Hindu. He added: “The CPEC can then be renamed as China-South Asia corridor benefiting all participants.”

Nevertheless, Professor Long noted that though the CPEC is a link between the land corridor of the Silk Road and the MSR, “its emergence was more important to Pakistan than to China.”