(Credit: guardian.com)

Khan is contemplating the fate of Nawaz Sharif, three-times prime minister of Pakistan, and one of the most prominent politicians linked to the Panamanian law firm Mossack Fonseca. According to the leaked files published worldwide this month, Sharif’s children raised £7m in loans against four flats in Park Lane, London, owned by offshore companies. Sharif denies any wrongdoing, and his son says the family never tried to conceal their assets, but Khan insists the flats were bought with money plundered from the Pakistani people.

For Khan, it feels like a vindication. It has been 20 years since one of the world’s most famous sportsmen reinvented himself as a pious political campaigner against corruption. For much of those two decades, he has been railing against Pakistan’s rulers and how they spend and stash their money in the west. “When I was living in England I saw how those ministers lived – spending £100,000 in casinos, living in palaces [when Pakistan] doesn’t have basic facilities,” he says. “That’s why I called my party Movement for Justice.”

“But I couldn’t get anywhere because the ‘coalition of the corrupt’ would help each other. They would conspire to protect each other, even though they were in different parties.”

Now Khan is back in London, partly to find investigative firms to look into Sharif’s accounts and “follow this money trail”.

“I wasn’t surprised by the Panama Papers,” he says, his eyes narrowing, “but I was happy. It is disgusting the way money is plundered in the developing world from people who are already deprived of basic amenities: health, education, justice and employment.

“This money is put into offshore accounts, or even western countries, western banks. The poor get poorer. Poor countries get poorer, and rich countries get richer. Offshore accounts protect these crooks.”

In comparison, the disclosures about politicians in the west, such as the financial dealings of the Cameron family, seem tame, he says. “You are talking about £30,000. I am talking about millions. You have to put it into perspective: we are sinking. “In Pakistan [almost] 50% of our population has stunted growth because they don’t have enough food. When the elite steal money from here – and I mean steal, not just avoid paying tax – then they can’t hold on to power.”

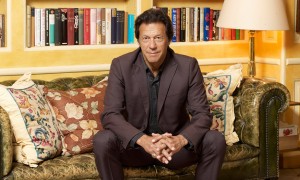

Khan is soon broadening his theme to global injustice and “world elites being able to siphon off money”. Then he breaks off – to thank the butler who has come in with a tray of coffees. The interruption highlights what an odd place this is to discuss the ills of elitism. True, Khan, in his grey suit and dark shirt, is the smartest thing in the room; the sofa has a rip, there are empty yoghurt pots, dumbbells are scattered in the corner (a sign that Khan is visiting his teenage sons). We we are sitting in what you might call a granny flat. Albeit one attached to a stately home.

Ormeley Lodge, a mansion on the edge of Richmond Park in south-west London complete with orchards and a tennis court, is home to Lady Annabel Goldsmith. It was bought by Sir James Goldsmith – a committed non-dom whose £1.2bn fortune was put into an overseas trust for his children after he died – the father of Khan’s first ex-wife Jemima.

It is here that Khan’s old ties clash most obviously with his new role as a conviction politician who admires Jeremy Corbyn and talks of “westoxification”. More than a decade after his first divorce, Khan still stays with the Goldsmith family when he is in London. The affection seems mutual – in the library there is a framed photograph of Khan laughing with his ex-wife and a golden-haired son. He tells me cheerfully that he and Lady Annabel – whose eponymous nightclub is the only one the Queen has ever visited – are old “gossip pals … When I come, we catch up at breakfast on all the gossip I have missed for six months.”

It must have been a long breakfast. Last month, Annabel’s son Zac Goldsmith, Conservative MP for Richmond Park and North Kingston, launched his official bid to become London mayor. On 23 March, Khan wrote a flurry of tweets supporting his ex-brother-in-law. It’s a curious endorsement. Goldsmith has been been dogged by questions over his finances, from the offshore trust set up by his father to the non-domiciled status he held before becoming an MP. But more surprisingly, he has been accused of running a divisive smear campaign against his Labour rival, Sadiq Khan. A former human rights lawyer, Sadiq Khan was dubbed a “radical” and accused of “providing cover for extremists”. Leaflets sent to Hindu and Sikh voters implied their jewellery was not safe with the MP for Tooting, south London.

Does the former cricketer know what has been going on? As a devout Muslim, he has just been discussing increasing Islamophobia in the UK with me, and looks uncomfortable at the mention of the campaign. “I am completely cut off from UK politics and this mayor race,” Khan says quickly, “and I haven’t met Zac [on this visit]. What his campaign is, I have no idea.”

But he is robust in his defence of Goldsmith’s character – praising his environmental credentials and his character. “My backing of Zac is purely [based] on knowing him for 22 years and urging him to go into politics.” Does he think he is Islamophobic? “Of course not. I think of anyone, he will be very fair with minorities, I think he is very just.” You don’t think he would use inflammatory rhetoric for political gain? “I don’t know the context he has come up with this. I don’t know Sadiq Khan at all, so I can’t comment. But I don’t think that is a line of attack anyone should take.”

After we meet, Khan releases a statement in response to similar questions from Channel 4, saying he has now read the campaign literature and believes the campaign is being conducted with “integrity, honesty, and by appealing to Londoners regardless of their colour or creed”.

Zac Goldsmith’s financial affairs, he says, show nothing more than a “fault in the system … Zac didn’t set up this company, and he didn’t do anything illegal. I know he is honest.”

If Khan is a loyal friend, his belief in Nawaz Sharif’s guilt is equally implacable. He hands me stacks of papers, which he says back up his claims. He cites inconsistencies in Sharif’s rebuttals over his children’s links to offshore companies.

In April 2000, after Sharif was toppled and put in prison by the country’s then military leader, Pervez Musharraf, allegations of corruption resurfaced. Sharif and his family say such claims are politically motivated. In a statement released after the Panama Papers came to light, the family claimed that as Sharif’s sons have lived abroad for more than two decades, they are not eligible to pay tax in Pakistan. Sharif’s daughter, who does live in Pakistan, was named simply as a trustee of one corporation.

Last weekend, Sharif arrived in London for medical treatment, which the New York Times claimed prompted rumours he would not return to the country until the investigations are over (a photo surfaced of him on Twitter shopping in Savile Row). Sharif has agreed to launch an inquiry headed by a retired judge; Khan is pushing for a sitting judge. If this fails, Khan says, he will begin street protests.

But will this change anything? Pakistani politics are renowned for their murkiness: Sharif was convicted of corruption in 2000, but claims allegations against his family are always politically motivated. Khan insists that this time, no one will look away. “The media and the people are on one page – they want [corruption] to be exposed. Military dictators have physical authority. Kings have physical authority, but democrats rule by moral authority. When you lose that, you can’t rule.”

Moral authority is something 63-year-old Khan is still banking on after a bruising few years. His cricketing skills and good looks won him poster space on the walls of a generation of Pakistani boys and girls, and undying devotion when he won them the World Cup for the first time in 1992. Educated at Pakistan’s version of Eton, Aitchison college, in Lahore, and Oxford, he fitted seamlessly into London society, mingling with royals and clubbing with Mick Jagger. But his political career has been more chequered.

After years of being seen as too naive for politics, in the run-up to his country’s 2013 elections he was drawing crowds of hundreds of thousands, inspired by his vision of a “new Pakistan”. Yet Sharif was elected for the third time. In 2014, Khan organised a public demonstration against the elections, whose legitimacy he questioned (although most international observers believed they were fair). Four months later, the protest was still continuing, but after clashes with police and fears the army would be called, it was far from a resounding success.

Like Sadiq Khan, Imran Khan, too, has faced claims that he is an extremist. His fierce opposition to drone attacks, and emphasis on dialogue with the Pakistani Taliban in the face of their brutal tactics, led to his being dubbed “Taliban Khan”. The militants even asked him to represent them in peace talks. Yet Khan laughs at this caricature. “I have always been anti-war. I don’t believe that Bush line: ‘You are either with us or against us’.

“There is a reason people pick up a gun, but you have to talk to them to find that out. You should go after the specific people responsible for killing – but in Pakistan you are dealing with 50 different groups who call themselves the Taliban; within that will be some who can be reconciled with.”

Most recently, Pakistani liberals despaired when Khan’s party seemed to oppose February’s landmark women’s protection bill. At issue was the fact that Khan had consulted a religious council for advice on the bill. It was a decision, he says, that was based on pragmatism: if the legislation was declared un-Islamic, it would become impossible to implement whether or not it was passed. “Our society has become so polarised, thanks to the war on terror. If they say: ‘This is Islam under threat’, then it harms your ability to reform your society.”

Khan’s personal life has been as turbulent as his recent political life and the subject of obsessive interest. He recently split from his second wife after 10 months. Writing in the Guardian, Reham Khan, said the experience had been traumatic. “I went and got married to the strongest man in the land, idolised by millions, only to face a barrage of abuse [from the public].”

Khan, in comparison, seems unscathed, saying “second marriages are not easy” and joking about trying again. “I am saying this as someone who, in his 63 years, has only been married for 10 years; but being married is better than being a bachelor – even for someone whose bachelor life was the envy of a whole generation.” With his ambition of leading Pakistan tantalisingly close, he says he has no regrets. “I could have lived off cricket, but you need a passion in life. The more you challenge yourself, the more exciting life is.”