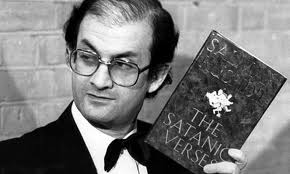

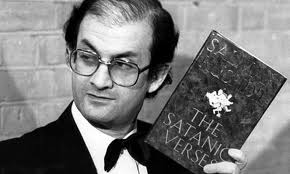

Valentine’s Day 1989 had nothing to do with love for Salman Rushdie. He “hadn’t been getting on with his wife, the American novelist Marianne Wiggins,” but that was nothing compared with the news from Iran, where the Ayatollah Khomeini made an announcement that plunged Rushdie into more than a decade of fear, sequestration and flight. “I inform the proud Muslim people of the world,” Khomeini said, “that the author of the ‘Satanic Verses’ book, which is against Islam, the Prophet and the Koran, and all those involved in its publication who were aware of its content, are sentenced to death.”

Not long after the proclamation of this fatwa, the British police who had been protecting Rushdie told him that he needed an alias, not only for receiving payments and writing checks without being identified but “for the benefit of his protectors,” who “needed to get used to it, to call him by it at all times, when they were with him and when they weren’t, so they didn’t accidentally let his real name slip . . . and blow his cover.” After some thought Rushdie “wrote down, side by side, the first names of Conrad and Chekhov, and there it was, his name for the next eleven years”: Joseph Anton. These “were his godfathers now,” and “it was Conrad who gave him the motto to which he clung as if to a lifeline . . . ‘I must live until I die, mustn’t I?’ ”

Thus the title of this, Rushdie’s memoir of his entire life, but mainly of those more than 11 years of torment, years often made bearable by the friendship and love of others, yet years unceasingly under the threat of the dire unknown, while Rushdie was squirreled away in secret London hideaways and remote farmhouses. For anyone it would have been terrifying, but for this proud and passionately sociable man it was degrading as well:

“To hide in this way was to be stripped of all self-respect. To be told to hide was a humiliation. Maybe, he thought, to live like this would be worse than death. In his novel ‘Shame’ he had written about the workings of Muslim ‘honor culture,’ at the poles of whose moral axis were honor and shame, very different from the Christian narrative of guilt and redemption. He came from that culture even though he was not religious, and had been raised to care deeply about questions of pride. To skulk and hide was to lead a dishonorable life. He felt, very often in those years, profoundly ashamed. Both shamed and ashamed.”

As that passage indicates, Rushdie has chosen to tell his story in the third person: to write not about Salman Rushdie but about Joseph Anton, the person who for more than a decade was himself yet not quite himself. It takes a few pages for the reader to get used to this, but it works: It eliminates the temptations of self-pitying bathos (temptations that surely must have been severe) and allows Rushdie to maintain a certain clinical distance from himself. He further intensifies this effect by abandoning, for the most part, the elaborate, fanciful, quasi-poetic style that characterizes most of his previous work (including “The Satanic Verses”) and to write, instead, in a plain prose that by its severity makes his ordeal all the more palpable.