After his recovery from GBS, Jawaid & I took walks in Anacostia Park to help his nerves gain full recovery. This photo was taken three weeks before the cowardly attack on him. A day before that incident on March 1, we had resolved to speed up the exercise process to help him regain full strength. It was also meant as a prelude to our trip back home.

If only Ignorance had not been Bliss

Barely a month before the attack on him, Jawaid sat in his living room, blissfully unaware of the evil that was being plotted underneath our condo unit. After decades of hard struggle, the `American dream,’ of finding work in one city.. and supporting near and dear ones.. had become a reality. The tranquility on his face was emblematic of the kindness in his heart and the good which he searched in every human being.

MEMORIES

Like yellow falling leaves on a warm summers eve,

Flutter and fall on fading heaps,

The winds of time swirl them aloft,

And light them to the eye in sunny beams,

So memories flutter before the eye,

Of past tears,

And past laughter,

And I quiver like a boat tied to the shore,

That can glide on roving waves no more.

WAIT JB, DON’T SAY GOODBYE

I wandered through the earth,

My heart was heavy with yearning,

My spirit scoured the angry seas to find a sorrow bearer,

The earth I tread shall cover soon my unfulfilled soul,

For death is the only peace,

That follows the torture of desire,

I wandered lone in search of God through the blindness of the earth,

If the earth has seductive lights, why hast thy no guide?

I walked all day to the sun but thy let thy curtain fall,

Oh let me die that I may see,

And rest my aching soul

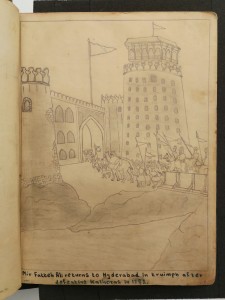

The British find Allies in the Conquest of Sindh in 1843

After the conquest of Sind in 1259/1843, the British attempted to subjugate neighbouring Baluchistan, in which the Aga Khan again helped them militarily and diplomatically. From Jerruk, where the Aga Khan was staying after February, 1843, he contacted the various Baluchi chieftains, advising them to submit to the British rule. He also sent his brother Muhammad Bakir Khan together with a number of his horsemen to help the British against Mir Sher Khan, the Baluchi amir.

Soon afterwards, the Aga Khan I was given a post in Jerruk to secure the communications between Karachi and Hyderabad. Charles Napier writes in his diary on February 29, 1843 that, “I have sent the Persian Prince Agha Khan to Jherruk, on the right bank of the Indus. His influence is great, and he will with his own followers secure our communication with Karachi. He is the lineal chief of Ismailians, who still exist as a sect and are spread all over the interior of Asia.”

H.T. Lambrick writes in “Sir Charles Napier and Sind” (London, 1952, p. 157) that, “Bands of Baluchis had plundered most of the wood and coal stations on the Indus, interrupted the mail route to Bombay via Cutch, and also the direct road to Karachi, whence supplies and artillery had been ordered up. With a view to reopening communications with Karachi, Sir Charles sent the Agha Khan to take post at Jherruk with his followers, some 130 horsemen.”

On March 23, 1843, the Aga Khan and his horsemen were attacked by the Jam and Jokia Baluchis, who killed some 70 to 72 of his followers, and plundered 23 lacs of rupees worth of the Aga Khan’s property. Napier, in April and May, 1843, sent warnings to the Jam and Jokia Baluchis, asking to return the plunder of the Aga Khan and surrender. In May, 1843, Napier ordered his commander at Karachi to attack and recover the property of the Aga Khan, which was done.

The encounter of Jerruk had been equated by the Aga Khan I, according to the native informations, with that of the event of Karbala. In Jerruk, some 70 to 72 Ismaili fidais had sacrificed their lives in fighting with the enemies of their Imam, and their dead bodies were buried on that spot. According to the report of “Sind Observer” (Karachi, April 3, 1949), “Seventy dead bodies of Khojas buried 107 years ago at Imam Bara in Jherruck town, 94 miles by road north-east of Karachi, were found to be fresh on being exhumed recently in the course of digging the foundation for a new mosque for the locality, a Sind government official disclosed on Saturday. The bodies which lay in a common grave were again interred another site selected for the mosque. The Khojas were believed to have been murdered in a local feud 107 years ago according to local tradition in Jherruck.”

It was with the approval of the British government that in 1260/1844, the Aga Khan sent Muhammad Bakir Khan to capture the fortress of Bampur in Iranian Baluchistan. Later, he also sent his other brother, Sardar Abul Hasan Khan, who finally occupied Bampur and won other successes in Baluchistan, while Muhammad Bakir had been relieved to join the Aga Khan in India.

The Aga Khan built his residence at Jerruk, resembling the style that of the Mahallat. Jerruk, a town about 89 miles and 2 furlongs from Karachi via Gharo, Thatta and Soonda; is 150 feet high from the Indus level, having two hills blanketing the town from two sides. About 300 to 350 Ismailis lived in Jerruk, and the Aga Khan I made it his headquarters

http://www.ismaili.net/histoire/history08/history809.html

Archives and Manuscripts at the Bodleian Library

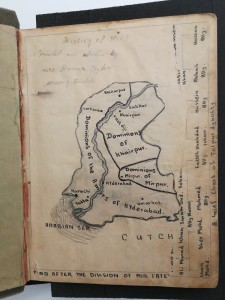

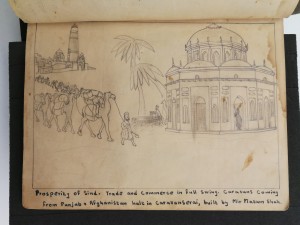

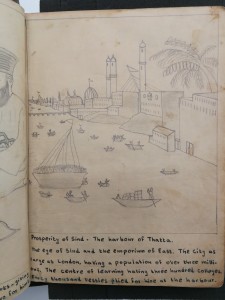

We have recently received the generous donation of an illustrated history of the Mirs of Sindh, given in memory of its author and illustrator Mrs. Amina G. Hyder Khaliqdina (1919 -1959).

Amina’s family have written an account of her remarkable story and kindly given permission for it to be posted here.

Amina was born on 19th April 1919 in Hyderabad, Sindh (presently a Province of Pakistan) to a middle class educated family. Many male members of her family were well-educated, including her grandfather and uncles, and some of them were civil servants of the British government.

Amina was part of the Muslim Shia Ismaili Community, which had emphasised female education. However, in Sindh education opportunities were limited especially for women.

After losing the battle of Miani with the East India Company in 1843, the Emirate of Sindh lost its independent status and was included as a part of the Bombay Presidency. This was the punishment for Sindh confronting the East India Company and, consequently, for many years Sindh remained underdeveloped. Infant mortality was high. Amina herself was the only survivor from seven births. There were only a few educational institutions within Sindh and for higher education one had to correspond with Bombay University. This made it socioeconomically difficult, especially for women, to achieve higher education.

Within this environment Amina achieved matriculation from Bombay University – the first woman in the family – perhaps one of a very few in Hyderabad, Sindh.

By 1936 Sindh had separated from the Bombay Presidency and with that a new chapter of development of Sindh began. Hyderabad again became a culturally bustling town. This was mainly due to Hindu Divans who worked on Plantations in the Caribbean and brought wealth to Sindh. They promoted art and culture. Yet female education was scarce especially for muslims.

Amina was appointed as head of Art section in Madras -Tul – Banat school. We know very little about Amina’s interest in Art and her degree/diploma related to this book due to her untimely death. According to Amina’s mother, she started the artwork in this book before she started her employment and carried on sketching long after her first two children were born. Considering the lack of resources libraries, etc., and limited access to Bombay University, her book is evidence of her perseverance. The book is written in English. It shows her competence in multifarious skills.

In addition, she was a champion for promoting education, regardless of cast, religion or gender. We know that she used to gather together children from the neighbourhood, motivate them, and took them to school. There are many doctors, teachers, and artists who are her ex-students in Sindh and will testify to this fact. She was a pioneer in establishing a reading room and a library for women in Hyderabad so they could read and have literary discussions.

Amina was married on 7th May 1942 and bore seven children. She continued working until her fourth child. The concept of a working mother was not very popular in those days but her quest for knowledge and passing knowledge to others overcame all obstacles. She was a positive influence to her husband too and encouraged and supported him. He became Chief Auditor and Director of Finance for the Province of Sindh (Pakistan).

Politically, the 1930s to 40s was a turbulent period in India. There was the struggle for independence on one hand and, on the other, muslims were demanding equal rights or a separate country. Fortunately Sindh was a religiously tolerant province. There was hardly any evidence of Hindu-Muslim conflict. Her own family was divided: some were supporters of Jinnah’s Pakistan, and others supporters of Gandhi and Congress. But Amina was a supporter of Sindh. She wanted generations to remember the former glorious period of Sindh, its independence, the dark period of Mir’s internal conflict, and the resulting victory of Charles Napier of East India company – who was knighted as a reward of conquering Sindh. Atrocities committed on Sindhis during the battle of Miani were truthfully acknowledged by Sir Charles Napier himself, ”If this was a rascality it was a noble rascality”

Amina’s pictorial description and historical perspective on the Mirs of Sindh is not only a tribute to her Motherland but a testimony to her intellectual vigour, academic pursuit and her artistic abilities. Sadly, her sudden and untimely death on 23rd May 1959, at the tender age of 40 years, deprived not only Sindh of one of her zealous devout daughters, but her parents lost their only child, and her seven young children lost a loving mother and her husband lost a supportive and beloved wife.

Peshawar school attack game withdrawn after uproar

A video game based on the 2014 Taliban school massacre in which at least 132 children were killed in Pakistan’s northwest city of Peshawar has been withdrawn after triggering social media uproar and backlash.

The game, “Pakistan Army Retribution”, was released by the Punjab IT board on Google Play, and invited the player to step into the shoes of a soldier shooting Taliban attackers in a school’s hallways.

It is inspired by Pakistan’s deadliest terror attack that saw seven Taliban gunmen storm the Army Public School (APS) in December 2014.

They shot students and teachers in cold blood and occupied the school for hours until they were killed by the army.

The assault shocked Pakistan and emotional ceremonies marking the anniversary were held across the country last month.

The game was released on Google Play several weeks ago but only came into the limelight after an article lampooning the game in Pakistan’s Dawn newspaper appeared on Monday, making social media users lambast its makers for exploiting the tragedy.

By Monday afternoon, the game was no longer available on Google Play.

Umar Saif, the chairman of the Punjab Information Technology Board, a government body, confirmed that the game was no longer available.

“It wasn’t very well done and it was in poor taste,” said Saif. “In hindsight it was not a good thing to do.

“APS was a watershed for Pakistan, so we had the idea of using it as a theme to promote peace, tolerance and harmony. The plan was to show children that the best weapons are the pen and the book.”

Saif added that the game was produced by an independent company that had “misunderstood the brief” and the IT board “messed up with this particular game”.

Imposter Express Tribune Facebook page spreading fake news

The Express Tribune has been inundated with hundreds of messages from our readers and well-wishers regarding a fake Facebook page that is impersonating the publication.

The Facebook page, which has stolen design elements from us, including The Express Tribune’s trademark red ‘T’, has garnered over 3,000 Facebook likes.

While we strive to remedy the problem, we thank our readers for informing us about the serious violation of our intellectual property.

We have already reported the impostor page to Facebook and hope quick action will be taken against those who have sought to harm The Express Tribune’s image as a trusted news source across Pakistan and the world.

Unfortunately, there is only so much we can do at this time. The problem of fake news on social media platforms such as Facebook is a real and damaging one. In this case, it hurts not just The Express Tribune but also creates chaos and confusion among the public.

The Express Tribune’s official Facebook page has a verified blue tick and nearly 2 million followers.

Five ways Indians are dodging the ‘black money’ crackdown

From deploying ‘cash coolies’ to buying Rolex watches, Indians have found unique ways to dodge the government’s surprise move to withdraw high value bills in a bid to tackle widespread corruption and tax evasion.

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi sent shockwaves through the country by announcing on November 8 all 500 rupee ($7.30) and 1,000 rupee notes — some 85 percent of all bills in circulation — would cease to be legal tender within hours.

The announcement threw India’s cash-dependent economy into turmoil and triggered a mad rush among people with undeclared, unaccounted cash — so-called “black money” — to exchange old notes or use them to buy gold and luxury items.

Tax evasion is rife in India with many small businesses and professionals such as doctors and lawyers asking to be paid in cash to avoid taxes.

Only six people earning over 500 million rupees filed returns in 2012-2013, despite there being an estimated 2,100 ultra-wealthy Indians whose net worth exceeds $50 million.

But the government is cracking down and banks must report anybody depositing more than 250,000 rupees, while holding undeclared cash can lead to a penalty of double the tax owed.

1. Cash Coolies

There have been multiple reports of factory owners and businessmen asking staff — or even hiring casual labourers — to stand in bank queues and exchange cash for them before the December 30 deadline.

The initial over-the-counter currency exchange limit was 4,000 rupees but was later reduced to 2,000 rupees after the government said “unscrupulous elements” were paying the poor to queue to exchange their money.

The government also asked banks to ink people’s fingers — a tactic normally used to fight voter fraud — after they had exchanged bills to prevent them from queuing up again.

2. Rolex buying spree

Wealthy Indians rushed to make costly purchases with unaccounted cash soon after Modi’s announcement on November 8.

Several luxury retailers stocking brands like Rolex and Dior sent emails to clients stating their stores would be open until midnight that day, the Economic Times reported.

The daily said a leading global fashion brand store in Delhi remained open all night immediately after the move was announced, selling merchandise worth more than $150,000 in less than three hours.

3. Get gold

Some affluent buyers have reportedly been paying almost twice the market value for gold in old notes. Jewellers who had shut up shop for the day on November 8 reopened their stores within hours and were selling gold all night, local media reported.

Customers lined up outside jewellery stores in Delhi and Mumbai with bags of cash with one report saying they paid as much as 52,000 rupees ($762) per 10 grams of gold, almost double the going rate.

4. ‘Rent’ an account

Officials say they are keeping an eye on all cash deposits made into new “Jan Dhan” accounts which were opened by the government as a part of its financial inclusion scheme for the poor and farmers and which were designed for deposits such as welfare payments.

Following the withdrawal announcement, many of these accounts have seen deposits of thousands of rupees in a single day.

Local media have reported that corrupt individuals are “renting” these accounts to deposit their money in, only to withdraw it later.

5. Travel trick

In a sign of how desperate some Indians were to convert cash, a massive spike was seen in the number of railway ticket bookings after authorities said old bills could be used until midnight on November 11 to make reservations.

Most of these were advance bookings made using old notes.

Bookings can be cancelled at a later date with refunds paid out in new notes with only a small fee deducted.

This Remote Pakistani Village Is Nothing Like You’d Expect

PASSU, Pakistan — Sajid Alvi is excited. He just got a grant to study in Sweden. “My Ph.D. is about friction in turbo jet engines,” Alvi says. “I will work on developing new aerospace materials—real geeky stuff!”

Alvi’s relatives have come to bid him farewell as he prepares to leave his mountain village and study in a new country, some 3,000 miles away.

“We will see you again,” one of them says as they hang out in the potato field in front of Alvi’s house. “You know you won’t get far with a long beard like that. You look like Taliban!”

Alvi, dressed in low-hanging shorts and a Yankees cap, is far from a fundamentalist: He’s Wakhi, part of an ethnic group with Persian origins. And like everyone else here, he is Ismaili—a follower of a moderate branch of Islam whose imam is the Aga Khan, currently residing in France. There are 15 million Ismailis around the world, and 20,000 live here in the Gojal region of northern Pakistan.

I’ve been visiting Gojal for 17 years, and I’ve watched as lives like Alvi’s have become more common here. Surrounded by the mighty Karakoram Range, the Ismailis here have long been relatively isolated, seeing tourists but little else of global events. But now, an improved highway and the arrival of mobile phones have let the outside world in, bringing new lifestyles and opportunities: Children grow up and head off to university, fashions change, and technology reshapes tradition. Gojal has adjusted to all of this, surprising me every time I return by showing me just how adaptable traditions can be.

With these photos, I hope to add nuance to our understanding of Pakistan, a country many Westerners associate with terrorism or violence. People have suffered from this reputation, and many feel helpless in trying to change it. The Pakistan I’ve seen is different from that popular perception. I returned there this summer with my family and focused my attention on a young and forward-thinking community in Gojal, a place I know well.

I first came here in the summer of 1999. I was 25 and my girlfriend and I bought one-way tickets to Pakistan. We were looking for inspiring treks (the Karakoram Range has the highest concentration of peaks taller than 8,000 meters). Back then, we were among the roughly 100,000 foreign tourists to visit northern Pakistan each year.

We stayed for months, opening new passes, learning the language, and exploring the Karakoram, Hindu Kush, and Pamir. I kept returning, but over the years, I saw the number of fellow hikers plunge. The tourism department now records only a few thousand foreign visitors each year.

“Following the terrible September 11th attacks, anyone involved in tourism had to sell their jeeps or hotels; no tourists dared to come here anymore,” says Karim Jan, a local tour guide.

With each return visit, I noticed other changes. While outsiders were rare, the improved Karakoram Highway, now able to host vehicles other than Jeeps and 4x4s, brought in local tourists from south Pakistan, and southern cities became more accessible to the Wakhi.

“In these remote parts, our relationship to our honored guests has never changed,” Jan says. “You know, our kids go away to the cities, but deep down we are just mountain farmers living off the land. Sometimes we feel sadness for the way the Western world thinks of us, but we would rather joke about it than be bothered by it.”

The day after Alvi’s going-away party, we climb a nearby hill where young people are gathering. In the distance, we see the peak of Tupopdan—which means “sun-drenched mountain” in Wakhi—as it towers above a green oasis and the Passu village. A road winds through a barren valley—a branch of the old Silk Road. Beyond these peaks are the deserts and plains of Central Asia, China, and Afghanistan.

Some of the young men on the hill sport designer t-shirts, jeans, styled beards, and ponytails (hipsters know no boundary). Others wear the traditional white pants and long shirt. Four young men bring up a huge speaker and blast a mix of dancehall and traditional music.

As we dance, a group of girls watches us, laughing. Others ignore us, focusing instead on a game of volleyball. Alvi points to them.

“They are all going to school and most of them speak at least four languages,” he says, as our conversation switches between English, Wakhi, and Urdu. “We have a famous saying: If you have two children, a boy and a girl, but you can afford to educate only one, you must give the education to the girl.”

A few days later, Esar Ali, dressed in a suit and ready for a family wedding, climbs a boulder, away from the crowd. “The recent changes,” he says, discussing village life, “they come a lot from our education. Nowadays we go to universities outside of our villages, in the cities or abroad.”

“But they also come from this,” he adds, pointing to his phone. Smartphones and mobile data networks have changed how the people here relate to the outside world, and to their neighbors.

“I first saw Shayna in a town near my village,” Ali says. “There is a decent 2G reception there.”

“We started messaging, agreeing on a time to talk when no one is at home,” he says. “In our tradition, to be with someone is something sacred. So while we slowly establish our relationship, we never want to offend our elders. Phone or no phone, we have to keep our customs alive.”

Ali is now married to Shayna. This courtship would’ve been much different 10 years ago, but not because he wouldn’t have had a mobile phone. Back then, “our parents would pick the bride or groom,” he says. “But now it’s practically all love marriages, or rather arranged love marriages. We simply suggest to our parents the boy or girl we want to marry.”

There are two long lines in front of the wedding house; men on one side, women on the other. An elderly lady, her white veil flowing on top of an embroidered skullcap, welcomes me. She takes my right hand and kisses the top of it. I kiss hers in return; it’s the Wakhi way of greeting each other. I walk down the line, asking the traditional “How is your health, my sweet mother?” to each of the ladies.

It’s a typical mud house, and inside, young men are standing next to a gigantic pot of food; Ali steps up and says he hopes I’m hungry. “They are making bat for over 200 people,” he says, referring to the porridge-like food in the pot. “We will eat that with boiled sheep meat and lots of chai.”

My wife and two young sons are outside somewhere playing cricket. When I look for them, I see my wife being pulled into a group selfie with the young bride and her friends. They ask me to join in.

Here, there is no such a thing as an uninvited guest. We’re joined by our friends Emmanuelle and Julien from Paris, and they’ve brought their two daughters. “With the current world situation, people thought we were joking when we were telling them that we were going on holiday to Pakistan,” Emmanuelle says. “We got worried too and almost called off the trip.”

But Emmanuelle says she’s glad she didn’t cancel. The scene is nothing like what she assumed.

“I mean, if you ask someone back home to imagine life in a remote mountain region in Pakistan, do you think they will picture this? This place is really doing something to me; it’s making my soul grow.”

Coming here again and again, this tight community always humbles me. Now, as external changes increasingly permeate daily life and relationships, Gojal has planted a foot in the modern world while retaining its traditions and ability to inspire. Traveling in places that we only know little about—or hold wrong ideas about—puts life into perspective. I hope the grace of this place will touch many more people.