JAVED BHUTTO was shot and killed March 1 as he unloaded groceries from the trunk of his car in the parking lot of his condo complex in Southeast Washington. His alleged killer was his neighbor, a man who had killed someone else in another unprovoked shooting but had been found not guilty by reason of insanity, and was released after 17 years of treatment at St. Elizabeths Hospital. He had been deemed safe to be released to the community, and he was supposed to have been closely monitored. Continue reading “D.C. must provide answers on the unprovoked killing of Javed Bhutto”

No sane reason Hilman Jordan was let out of a D.C. mental hospital 17 years after shooting a man. Now he’s accused of killing again.

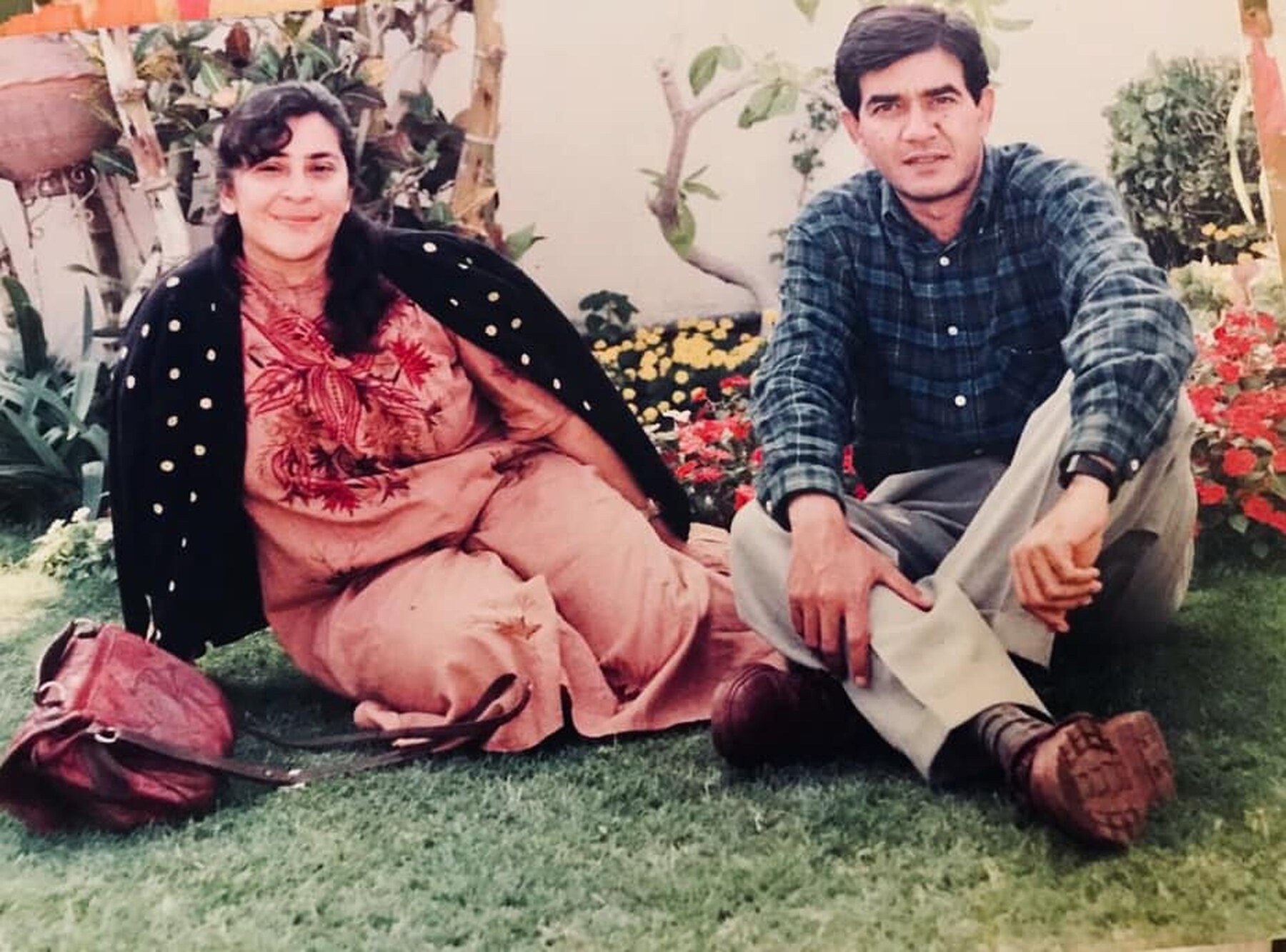

Javed Bhutto, a caregiver to mentally disabled adults, got home from work about 11 that morning with bags of groceries in his Toyota Corolla. After his overnight shift at a residential facility, he had stopped in a supermarket with a list from his wife. In the parking lot of the small condo complex where the couple lived, he stepped out of his car in the chill March air, opened the trunk and reached for his bundles. Continue reading “No sane reason Hilman Jordan was let out of a D.C. mental hospital 17 years after shooting a man. Now he’s accused of killing again.”

Pakistani philosopher killed by suspect with history of violence, mental illness

The Southeast D.C. man charged with first-degree murder for the shooting of his neighbor, Jawaid Bhutto, 64 — prominent Pakistani philosopher and scholar — was found not guilty by reason of insanity for a previous homicide in 1998.

Court documents reveal that Hilman Jordan, 45, who is currently being held without bond for the murder of Bhutto, was indicted by a grand jury 21 years ago for shooting and killing his cousin.

The documents say Jordan shot and killed his cousin, Kenneth Luke, on August 7, 1998. He was indicted later that month on charges of first-degree murder while armed, possession of a firearm during a violent crime and carrying a pistol without a license.

Jordan was committed to Saint Elizabeth’s Hospital on October 1, 1999. In 2003, the court began to order his gradual conditional release, including visits to his mother’s house on Christmas Day, New Year’s Day and Martin Luther King Jr. Day.

Jordan violated the conditions of his gradual release in 2005 when he obtained a gun from his family home and carried it to St. Elizabeth’s with the intent to kill a peer.

That violation sparked his transfer to a maximum security ward, where he remained for the next five years.

In January 2015, the government consented to a court order providing Jordan with an expanded conditional release, including overnight visits with family, unaccompanied community travel and eventual full convalescent leave.

The hospital told the court he had “sufficiently recovered from his mental illness to be granted an expansion of his conditional release privileges without posing a danger to himself or others.”

The terms of the January 2015 order prohibited Jordan from possessing firearms, or consuming alcohol or illegal drugs.

Jordan fatally shot Bhutto on Friday, March 1 around 11 a.m. in the parking lot of 2610 Wade Road S.E. — the apartment building where Bhutto resided with his wife, journalist Nafisa Hoodbhoy.

Jordan lived on the second floor of the building. Hoodbhoy told NBC Washington her husband had complained about the odor of Jordan’s smoking wafting into his residence and disturbing his sleep.

Police say they have been able to observe the entire shooting from beginning to end thanks to surveillance video. Charging documents say the video shows Jordan approaching Bhutto and firing a handgun as Bhutto exited his car in the parking lot.

Police say a search warrant of Jordan’s apartment uncovered, among other things, a 9 mm handgun and a marijuana cigarette. He was taken into custody on the balcony of his apartment.

Family members of Bhutto say his death is being widely mourned in his home region of Sindh, Pakistan. He was chairman of the philosophy department at Sindh University.

Jordan is being held without bond and is scheduled for a preliminary hearing in D.C. Superior Court on March 12.

Situationer: The killing fields

IN the heart of Mastung city, the Shaheed Nauroz Football Stadium is located on a huge, walled tract of land. This was where, in 2011, the All Pakistan Football Tournament was held. Siraj Raisani, younger brother of then chief minister Nawab Aslam Raisani, was invited as the chief guest to the final.

At the time, Baloch separatists held sway in the district, and they had warned Siraj Raisani of dire consequences if he visited.

As the final match started, locals say, he arrived with a tribal force of 200 men and as many security personnel. There were around 2,000 spectators in the stadium. All through the course of the match, Siraj’s younger son stood by him in guard; it was during the award distribution ceremony that tragedy struck.

A hand grenade was hurled at Siraj Raisani, and while he escaped the assault narrowly, his son Hakmal was badly injured. The young man succumbed to his injuries on July 29, 2011, while being moved to Quetta’s Combined Military Hospital. In addition to Hakmal, another man was killed while 39 more were injured.

Following the death of his son, which was claimed by Baloch separatists, Siraj Raisani sided completely with the state against the insurgents. Subsequently, he launched his own party, the Balochistan Muttahida Mahaz. In recent times, this was merged with the Balochistan Awami Party (BAP), and Siraj was contesting elections in PB-35 against his brother, Aslam Raisani.

In Mastung, politicians campaigned actively for the first time, holding rallies and corner meetings. But elections in PB-35 have been cancelled after the killing of Siraj Raisani.

Shabbir Baloch in Mastung says that he became fearful when he witnessed the vigorous electoral campaign here. “I told my colleagues that the elections would be bloody,” he recalled. “Graffiti, allegedly inscribed by banned Baloch outfits, appeared in the bazaar warning people to stay away from Siraj’s electoral campaign.”

On July 13, Siraj Raisani was continuing with his electoral campaign; a week ago, he had inaugurated the BAP office in Mastung. Finally, party workers set up tents in Dringrah. Candidate Usman Pirkani organised this public meeting, and had asked his Pirkani tribesmen from the remote areas of the district to attend.

A bomb explosion ripped through the crowd at 3:50pm. “I was in the crowds,” remembers Asif Pirkani. “Many of those standing died on the spot, and parts of their bodies rained down on me. I fled the destroyed tent.”

Dringarh is a vast but thinly populated area of 10 villages, with the people belonging to different tribes. It was here that in 2014 a bus carrying Hazara pilgrims was targeted by a suicide bombing that left some two dozens dead. That destroyed bus lies to this day in front of the Levies Station.

Currently, there is tight security in Dringarh and people are reluctant to talk. The victims of the July 13 attack came mostly from outside — the casualties from this area constitute mainly children. The majority of the people killed in the Mastung bombing are from the Pirkani tribe, who are mostly nomads — many don’t even have national identity cards. They did not know who Siraj Raisani was, and Usman Pirkani — who had instructed them to attend the rally — did not himself go. Mohammad Zia, in his late ’60s, lost two sons, along with his nephew. They knew nothing about politics, he said.

One of the injured is Mohammad Azim Pirkani, who is being treated in the trauma centre of the Quetta Civil Hospital. “Everyone one was going, so I joined in,” he said. Three of his colleagues were killed and another was injured. Similarly, another injured man is Rafique, who is a Sindhi man from Quetta. He is not a local of Mastung, but had gone there as a new member of the BAP.

Why did Usman Pirkani himself not go? He said that he was busy with his own corner meeting in Quetta.

The Pirkani tribes are fed up with burying their dead. Qasim Pirkani says they buried 15 men on the first day alone. By local journalist Attaullah’s account, in some places in Mastung, room in graveyards ran out.

Though this bombing was one of the biggest attacks in the country, the day it occurred it was not given adequate coverage by the media. And, beyond Balochistan, hardly anyone knew who Siraj Raisani was. It was only when COAS Qamar Javed Bajwa attended his funeral that the media tuned in.

The tragedy of the Raisani family stems partly from the coincidences: like his son Hakmal, Siraj was injured in an explosion in the same month, in the same district. He, too, died on the way to Quetta’s Combined Military Hospital.

At first, it was believed he was targeted by banned Baloch outfits, but security forces said that these organisations do not have the capability to carry out such attacks. After that, the so-called ‘Islamic State’ claimed responsibility. The security forces have reportedly taken robust action against IS and Lashkar-i-Jhangvi militants in Mastung.

Taliban Opponent in Pakistan Killed by Bomb as He Campaigns

PESHAWAR, Pakistan — A candidate from a political party opposed to the Taliban was killed in a suicide bombing late Tuesday as he campaigned in northwestern Pakistan, just weeks before the country goes to the polls.

At least 12 people were killed and dozens were wounded, several of them critically, police and hospital officials said. The death toll was expected to rise, officials said.

There was no immediate claim of responsibility, but immediate suspicion fell on the Pakistani Taliban, which has frequently attacked secularist politicians.

The attack raised concerns about the safety of candidates running in the July 25 general elections, and immediately cast a pall across Pakistan. It was the first such attack of this year’s campaign.

The candidate who was killed, Haroon Bilour, belonged to a prominent political family from Peshawar, the capital of northwestern Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Province.

Mr. Bilour, who was running for a provincial assembly seat, was at a campaign event late Tuesday night when the bomber detonated his explosives jacket, police officials said.

Mr. Bilour’s father, Bashir Ahmad Bilour, a prominent politician and a senior provincial minister, was killed in a suicide attack by the Taliban just months ahead of the last general elections, in 2013, not far from Tuesday’s explosion. Haroon Bilour’s son was wounded in the latest attack.

The Bilours belonged to the Awami National Party, whose opposition to the Taliban has made it a repeated target of the militants. Several of the A.N.P.’s leaders and at least 700 of its workers have been killed in the past decade.

The intensity of the attacks greatly affected the party’s ability to openly campaign and mobilize supporters in the last general elections and contributed to losses, party officials said. With the security situation significantly improved in the country in the last couple of years, however, members of the A.N.P. had hoped that they would be able to campaign in safety.

Haroon Bilour, the provincial information secretary of his political party, expressed such hopes in recent interviews with local news media. Mr. Bilour had survived at least two assassination attempts.

But late Tuesday, a suicide bomber managed to mingle with the supporters of Mr. Bilour as he arrived at a campaign event in Peshawar. “The suicide bomber was sitting and waiting for Haroon to arrive,” said Taj Muhammad Wazir, a local A.N.P. official.

The killing was widely condemned by Pakistan’s political leaders.

Imran Khan, the leader of Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf, condemned the attack and called for the state to provide proper security for the candidates.

“Yet another A.N.P. leader has sacrificed his life for the sake of peace and democracy,” Sardar Hussain Babak, the provincial general secretary of Awami National Party, said in a telephone interview.

“We have a long list of martyrs, and we will continue to fight against the forces of extremism and militancy.”

Mr. Babak, who is also running for elections, said the party leadership was getting threats from the Taliban on an almost daily basis.

“But the federal and provincial governments have failed to provide us with security,” he said. “We had made our own security arrangements.”

Salman Masood reported from Islamabad, Pakistan. Ihsanullah Tipu Mehsud contributing reporting from Islamabad.

‘May God Kill Your Own Son’: Bomb Rips Families Apart in Kabul

KABUL, Afghanistan — A suicide bomber detonated explosives in a crowd celebrating the Persian New Year in Kabul, Afghanistan, on Wednesday, killing 31 and leaving desperate family members searching among bodies and body parts for their loved ones’ remains.

The victims were strewn around the courtyard in front of the Ali Abad Hospital in Kabul, where relatives preparing for burials tried grimly to match trunks with limbs or heads with trunks, and doctors searched for anyone with a pulse.

While it was hard to know for sure, there were at least 10 dead just in that area, plus limbs, hands, and other pieces of flesh that were impossible to identify.

In one corner, lying face down on a staircase, was a boy named Mustafa of about 12, who at first glance looked alive. Then it was obvious that one of his legs was blown nearly off; a new black-and-white sneaker remained on the foot. His other leg was nowhere to be seen. For more than an hour no relatives appeared, until finally his mother and father arrived.

The father restrained his wife, trying to prevent her from seeing their son’s gruesome remains; she lashed out in anger. “Why are you alive?” she shouted at him. “Mustafa is dead, why are you alive?”

The bomber struck about noon Wednesday, according to Afghan government officials. The explosion happened right outside the hospital: The bomber was apparently stopped before reaching a Shiite shrine in the Kart-e Sakhi area of western Kabul, where Wahid Majrooh, the spokesman for the Ministry of Public Health, put the death toll at 31, with 65 others wounded.

The mother of Mustafa ripped off her head scarf in her grief, and rebuffed attempts by her husband and friends to put it back on. Beside herself, she engaged her dead son in desperate conversation.

“Mustafa, why have you left me alone? You were so happy to celebrate Nowruz, you so wanted to go. You said to me, ‘Look mother, you don’t know about style. I have dressed up, and my shirt matches my shoes.’ ” The shirt was also black and white.

The Islamic State claimed responsibility for the bombing, according to a report on its website, Amaq, cited by the SITE Intelligence Group. The Islamic State in Khorasan, the group’s local affiliate, has repeatedly targeted Shiites in the Afghan capital over the past year, most recently on March 9, when 10 people were killed in a suicide bombing at a Shiite mosque complex.

That blast set off protests by the Hazara minority, a long-oppressed ethnic group whose members are mostly Shiite.

In her soliloquy to her dead son, Mustafa’s mother reminded him of his sister, killed in an attack on the Kart-e Sakhi shrine last year. “When we lost Musqa, you came to me and you said, ‘Look mother, I am here, don’t worry, I am with you.’ But now, you are not, and what should I do without you?”

Judging from the survivors, the victims of Wednesday’s bombing were Sunnis, both Pashtuns and Tajiks, as well as Hazaras. Although the Sakhi shrine is mainly a Shiite institution, it had been regarded as a safe place because it was heavily guarded after the previous attacks on Hazaras. It had been a popular venue on Wednesday with many ethnic groups.

Nowruz is the beginning of the year on the Persian calendar, but it also serves as a celebration of the end of winter, the first day of spring and the beginning of the school year.

It’s associated with outdoor festivities and picnics, usually with many children present; it is also a traditional time to try on new clothes, and many dress in their finest to promenade in the city.

In the courtyard of the hospital, one family arrived to find three members among the dead: an older woman in a pink traditional Hazara dress; a young man named Sajad, already in a body bag; and a boy of about 4 or 5. The boy wore a new red shirt, and his father, wearing old clothes, lifted him in his arms. He seemed too shocked for words or tears as he laid him in an ambulance beside Sajad, his older brother.

Another relative came and shook the young man’s corpse, saying, “Sajad, please stand up, why won’t you talk to me? What will I say to your mother?”

A fashionably dressed young woman, about 22 years old, her hands decorated with elaborate henna tattoos, mourned an older brother; doctors lifted a corner of the sheet covering him so she could identify him.

She cried so hard that she ran out of tears, and began tearing her hair and scratching her face. “Lala jan,” she said, using the affectionate term for an older brother, “I want to come with you — I don’t want to be alive any longer.”

Many of those in the courtyard were furious, yelling at journalists to leave, and denouncing political leaders. Doctors joined in the anger, yelling for blood, for more ambulances, for medicine. Many in the crowd repeatedly chanted “Death to Hekmatyar,” referring to Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, the insurgent leader who last year made peace with the government, but is widely remembered as the “Butcher of Kabul” for his Hezb-i-Islami group’s relentless shelling of Kabul in the 1990s. There is no indication that his group was involved in Wednesday’s bombing.

Mustafa’s mother spent her ire on President Ashraf Ghani, with a maternal curse: “May God kill your own son so you will understand what it means to lose one.”

She looked confused when asked her name. “My name? I don’t remember my name, do I have a name?” Then she resumed screaming and cursing.

Her husband told her their younger son, Mujtaba, was on his cellphone. She composed herself and took the phone, telling Mujtaba not to worry, that his brother was still alive.

“Mustafa is just in the hospital, they are operating on him now, and he’s O.K.” She hung up and burst into tears again. Some young boys who knew her children were nearby, and she scolded them fiercely. “Do not tell Mujtaba his brother is dead. I don’t want him crying, too.”

Suicide attacks are now one of the biggest killers of civilians in Afghanistan, according to United Nations figures. A spokesman for the Taliban, Zabihullah Mujahid, said his group had not been responsible for the latest attack; it has similarly denied any role in previous attacks on Shiite religious targets.

The mother of Mustafa wiped her tears away with both hands, readjusted her head scarf, and resumed speaking to her dead son: “You see, Mustafa, I am O.K. now. I am not crying, like you asked me not to do when Musqa died. I’m here now, why are you not here?”

“When you left this morning, you wanted to go to the Sakhi Jan shrine, and you said you wanted to pray for your future, for a better future, for the future of our family, for Afghanistan,” she added. “Oh my Mustafa.

Body of MQM leader Dr Hasan Arif found in a car in Karachi

Professor Dr Hasan Zafar Arif, MQM-London’s deputy convener, was found dead in a car in Karachi’s Ilyas Goth area on Sunday, police said.

“The body of Hassan Zafar Arif, son of Maqbool Hassan, 70-72-years-old, was found from car number ANC-016, Lancer silver at Ilyas Goth,” station house officer at Ibrahim Hyderi police station confirmed.

“The body was shifted to Jinnah Postgraduate Medical Centre (JPMC),” he added.

The SHO said that the cause of death will be ascertained after an autopsy is carried out. “Further investigations are ongoing,” he said.

At JPMC, Dr Seemi Jamali said that no signs of torture or bullet wounds were found on the body.

She added that further details will come forward once the autopsy is complete. The body has been shifted to the mortuary to ascertain exact cause of death.

Senior Superintendent Police Malir Rao Anwar also said that no marks of torture were found on Dr Arif’s body.

Dr Arif was a former associate professor at the Philosophy Department in University of Karachi.

According to MQM legal adviser Advocate Abdul Majeed, Dr Arif was with him on Saturday evening but left earlier than usual as his daughter was leaving for London. Majeed said he received a call from Arif’s wife in the morning, saying he had not returned home. He was a resident of DHA Phase-VI.

He demanded that a proper inquiry be carried out into the death as the location where the car was found was not on Dr Arif’s route. “On Saturday evening, he drove the car himself from his office at Fareed Chambers to his residence in DHA. But his body was found in the rear seat of the car,” he added.

In October 2016, Dr Arif was taken into Ranger’s custody from outside the Karachi Press Club, where he was due to address a press conference along with other leaders of MQM-London.

He had been booked for allegedly facilitating and listening to a controversial speech of MQM founder Altaf Hussain in which he reportedly tried to outrage religious feelings, criticised the military establishment and asked his workers to extort money from the traders.

In April 2017, he was released from Central Jail Karachi after an Anti-Terrorism Court (ATC) issued his release order.

Dr Arif was an associate professor at the University of Karachi and a former fellow at Harvard University.

Benazir Bhutto assassination: How Pakistan covered up killing

Benazir Bhutto was the first woman to lead a Muslim country. The decade since an assassin killed her has revealed more about how Pakistan works than it has about who actually ordered her death.

Bhutto was murdered on 27 December 2007 by a 15-year-old suicide bomber called Bilal. She had just finished an election rally in Rawalpindi when he approached her convoy, shot at her and blew himself up. Bilal had been asked to carry out the attack by the Pakistani Taliban.

Benazir Bhutto was the daughter of Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, Pakistan’s first democratically elected prime minister. His political career was also brought to a premature end when he was hanged by the military regime of General Zia-ul Haq. Benazir went on to become prime minister twice in the 1990s, but she was always distrusted by the military, which used corruption allegations to remove her from power.

At the time of her death she was making a bid for a third term as prime minister. The assassination caused widespread civil unrest in Pakistan. Bhutto’s supporters took to the streets, putting up road blocks, lighting fires and chanting anti-Pakistan slogans.

The general and the ‘threatening’ phone call

A decade later, the general in charge of Pakistan at the time has suggested people in the establishment could have been involved in her murder.

Asked whether rogue elements within the establishment could have been in touch with the Taliban about the killing, General Pervez Musharraf replied: “Possibility. Yes indeed. Because the society is polarised on religious lines.”

And, he said, those elements could have had a bearing on her death.

It’s a startling statement from a former Pakistani head of state. Normally military leaders in Pakistan deny any suggestion of state complicity in violent jihadist attacks.

Pervez Musharraf denies threatening Bhutto in a phone call

Asked whether he had any specific information about rogue elements in the state being involved in the assassination, he said: “I don’t have any facts available. But my assessment is very accurate I think… A lady who is in known to be inclined towards the West is seen suspiciously by those elements.”

Musharraf has himself been charged with murder, criminal conspiracy for murder and facilitation for murder in relation to the Bhutto case. Prosecutors say that he phoned Benazir Bhutto in Washington on 25 September, three weeks before she ended eight years in self-imposed exile.

Long-serving Bhutto aide Mark Seighal and journalist Ron Suskind both say they were with Bhutto when the call came in. According to Seighal, immediately after the call Bhutto said: “He threatened me. He told me not to come back. He warned me not to come back.

Musharraf said he would not be responsible for what would happen to Bhutto if she returned, Seighal told the BBC. “And he said that her safety, her security was a function of her relationship with him.”

Musharraf strongly denies making the call and dismisses the idea that he would have ordered her murder. “Honestly I laugh at it,” he recently told the BBC. “Why would I kill her?”

The deadly plot

The legal proceedings against Musharraf have stalled because he is in self-imposed exile in Dubai. Benazir Bhutto’s son and political heir, Bilawal, has rejected his denials out of hand.

“Musharraf exploited this entire situation to assassinate my mother,” he said. “He purposely sabotaged her security so that she would be assassinated and taken off the scene.”

The shot at Bhutto was followed by a bomb blast, which killed her.

While Musharraf’s case is on hold, others have been acquitted of the crime. Within weeks of the assassination, five suspects had confessed to helping the 15-year-old Bilal assassinate Bhutto at the behest of the Pakistani Taliban and al-Qaeda.

The first person to be arrested, Aitzaz Shah, had been told by the Pakistan Taliban that he would be the suicide bomber chosen to kill Bhutto. Much to his annoyance he was kept in reserve in case the attempt failed.

Two others, Rasheed Ahmed and Sher Zaman, confessed they were mid-ranking organisers of the conspiracy and two Rawalpindi-based cousins, Hasnain Gul and Rafaqat Hussain, told the authorities that they provided accommodation to Bilal the night before the killing.

Even though these confessions were subsequently withdrawn, phone records showing the suspects’ locations and communications in the hours before Bhutto’s murder seem to corroborate them. Hasnain Gul also led the police to some physical evidence in his apartment.

DNA from Bilal’s body parts gathered after his attack and tested in a US lab matched the DNA on some training shoes, cap and a shawl Bilal had left behind in Hasnain’s residence when he put on his suicide vest.

Five alleged plotters were acquitted earlier this year but remain in detention

Just a few months ago prosecutors were confident these alleged plotters would be convicted. But in September the case collapsed, with the judge declaring that procedural errors in the way the evidence was gathered and presented to the court meant he had to acquit them.

A dominant figure in Pakistani politics, Ms Bhutto served twice as the country’s prime minister, from 1988 to 1990 and from 1993 to 1996.

Young and glamorous, she successfully portrayed herself as a refreshing contrast to the male-dominated political establishment.

But after her second fall from power, she became associated in the eyes of some with corruption and bad governance.

Ms Bhutto left Pakistan in 1999, but returned in October 2007 after then-President Musharraf granted her and others an amnesty from corruption charges.

She was set to take part in an election called by Mr Musharraf for January 2008.

But her homecoming procession in Karachi was bombed by suspected militants. She survived the attack, which killed well over 150 people, but would be assassinated two months later.

The husband who became president

In Pakistan it is commonplace to hear people accuse Benazir Bhutto’s widower Asif Zardari of having organised the assassination. The claim is normally based on the observation that since he became president after her death he was the one who benefited most.

The conspiracy theorists, however, have not produced a single shred of evidence to indicate that Asif Zardari was in any way involved in his wife’s death. He has denied the allegation in the strongest possible terms. Those who make the allegation, he said, should “shut up”.

Asif Zardari faces another accusation: that despite having the powers of the presidency, he failed to properly investigate his wife’s murder.

Secret official documents relating to the investigation and obtained by the BBC show that the police inquiries were so poorly managed as to suggest they never wanted to find guilty parties beyond the low-level plotters they had already arrested.

The inadequacies of the police investigations were especially apparent after an unsuccessful attempt on Bhutto’s life on 18 October 2007 – two and a half months before she was killed.

Two suicide bombers attacked her convoy and killed more than 150 people. It remains one of the deadliest attacks ever mounted by violent jihadists in Pakistan.

The police work was so half-hearted that the bombers were never even identified.

The leader of the inquiry, Saud Mirza, has said that one man he established to have been a bomber had distinctive features, suggesting he came from a long-standing but small Karachi-based community of people of African descent.

This potentially significant clue about the suspected bombers identity was never released to the public.

Former President Zardari answers criticisms about the thoroughness of the police work by pointing out that he encouraged the work of Scotland Yard in relation to the murder and secured the appointment of a UN commission of inquiry to examine the circumstances of her death.

That inquiry, however, says it was repeatedly and blatantly blocked not only by the military but also Zardari’s ministers.

“There were many people in the establishment that we wanted to interview but they refused,” said Heraldo Munoz, the head of the UN commission.

And he said some of the obstacles came from the politicians as well as the military.

As the investigation progressed, he said, the safe house the UN team used was withdrawn, as were the anti-terrorist personnel who were protecting the UN staff.

A trail of dead people…

That there was a cover-up is beyond doubt. A BBC investigation found evidence suggesting that two men who helped the teenage assassin reach Benazir Bhutto were themselves shot at a military checkpoint on 15 January 2008.

A senior member of the Zardari government has told the BBC that he believes this was “an encounter” – the term Pakistanis use for extra-judicial killings.

Nadir and Nasrullah Khan were students at the Taliban-supporting Haqqania madrassa in north-west Pakistan. Other students associated with the seminary who were involved in the plot also died.

One of the most detailed official documents obtained by the BBC is an official PowerPoint presentation given to the Sindh provincial assembly.

It names Abad ur Rehman, a former student at the madrassa and bomb-maker who helped provide the suicide jacket used to kill Benazir Bhutto. He was killed in one of Pakistan’s remote tribal areas on 13 May 2010.

Then there was Abdullah who, according to the Sindh assembly presentation, was involved in the transportation of the suicide vests ahead of the Rawalpindi attack that killed Bhutto.

He was killed in Mohmand Agency in northern Pakistan in an explosion on 31 May 2008.

One of the most high-profile deaths related to the assassination was that of Khalid Shahenshah, one of Bhutto’s security guards. Shahenshah was within a few feet of Bhutto as she made her final speech in Rawalpindi.

Phone footage shows him making a series of strange movements for which no one has offered any reasonable explanation.

Although he kept his head completely still, he raised his eyes towards Bhutto while simultaneously running his fingers across his throat. Pictures of his gestures went viral and on 22 July 2008 Shahenshah was shot dead outside his home in Karachi.

The next victim was the state prosecutor, Chaudhry Zulfikar. A lawyer with reputation for high degrees of both competence and doggedness, he told friends he was making real progress on the Bhutto investigation.

Special prosecutor Chaudhry Zulfiqar Ali was killed in the capital

On 3 May 2013 he was shot dead on the streets of Islamabad as he was being driven to a legal hearing on the case.

… and one who turns out to be alive

Finally, there is a man who was said to be dead but, in fact, is still alive. In their confessions the alleged plotters said that on the day of the murder a second suicide bomber named Ikramullah accompanied Bilal. Once Bilal had succeeded in his task, Ikramullah’s services were not required and he walked away unharmed.

For years Pakistani officials insisted that Ikramullah had been killed in a drone strike. In 2017 chief prosecutor Mohammad Azhar Chaudhry told the BBC evidence gathered by Pakistani investigating agencies, relatives and government officials established that “Ikramullah is dead”.

In August 2017, however, the Pakistani authorities published a 28-page list of the country’s most wanted terrorists.

Coming in at number nine was Ikramullah, a resident of South Waziristan and involved, the list said, in the suicide attack on Benazir Bhutto.

The BBC understands that Ikramullah is now living in eastern Afghanistan where he has become a mid-ranking Pakistan Taliban commander.

So far the only people punished in relation to the murder of Benazir Bhutto are two police officers who ordered the murder scene in Rawalpindi to be hosed down.

Many Pakistanis regard those convictions as unfair, believing that the police would never have used the hoses without being told to do so by military.

It suggests, once again, a cover-up by Pakistan’s deep state – the hidden network of retired and serving military personnel who take it upon themselves to protect what they consider Pakistan’s vital national interests.

Pakistan Church Attacked by 2 Suicide Bombers

ISLAMABAD, Pakistan — Two suicide bombers attacked a church packed with worshipers on Sunday in southwestern Pakistan, killing at least nine people and injuring at least 35 others, several critically, officials said.

The Islamic State, also known as ISIS, claimed responsibility for the attack in Quetta, the capital of the restive Baluchistan Province, in the country’s southwest. The group’s Amaq News Agency posted a statement online Sunday that said attackers had stormed a church in Quetta, but gave no further details.

The assault raised concerns about the security of religious minorities, especially Christians, in a country with a dismal record when it comes to the treatment and protection of religious minorities, analysts say.

Pakistani officials denied that ISIS had an organized presence in the country, however, even though the terrorist group has claimed responsibility for several other attacks in Baluchistan in recent years.

“Law enforcement agencies have badly failed in protecting common citizens, and minorities in particular,” said Shamaun Alfred Gill, a Christian political and social activist based in Islamabad.

“December is a month of Christian religious rituals,” Mr. Gill said. “We had demanded the government beef up security for churches all over the country. But they have failed to do so.”

Christians make up at least 2 percent of the country’s population of about 198 million. Most of them are marginalized and perform menial jobs.

The attack, a week before the Christmas holiday, unfolded in the early morning hours at Bethel Memorial Methodist Church. About 400 people had gathered for Sunday service when an assailant detonated his explosives-laden vest near the door to the church’s main hall.

Another attacker failed to detonate his suicide jacket and was shot by security forces after an intense firefight, officials said.

Sarfraz Bugti, the provincial home minister, said the death toll could have been higher had the attacker managed to reach the main hall of the church, which is on one of the busiest roads in the city and near several important public buildings.

Local television networks broadcast images of terrified worshipers running out of the church as the attack was underway. Several young girls, wearing white frocks and holding red bags, could be seen fleeing the compound.

Witnesses told local news outlets that people, panicked and frightened, had rushed out after hearing a loud explosion, followed by the sound of gunfire outside.

As security forces moved inside the main hall after the attack, they were confronted by a scene of bloody destruction. Several benches and chairs were overturned. Musical instruments were turned upside down.

A Christmas tree with decorative lights stood at one corner, and blood was outside the door where the suicide bomber had detonated explosives.

Two women were among the dead, and 10 women and seven children were among the injured, hospital officials said.

Most of the injured were taken to the Civil Hospital nearby.

Quetta has been the scene of violent terrorist attacks recently, and a large number of military and paramilitary troops, apart from the police, have been deployed to maintain security.

Officials have repeatedly claimed that they have reduced violence in Baluchistan, a rugged and resource-rich province bordering Afghanistan and Iran. But the ease with which the attackers managed to carry out their assault on Sunday seemed to belie those claims.

“The army repeatedly claims that it has broken the backbone of terrorism in the country,” Mr. Gill said. “But terrorism is still very much present and destroying the lives of common people.”

An insurgency by Baluch separatists has long simmered in the province, and the Taliban and other militants maintain a presence in the region.

Some officials were quick to shift blame toward Afghanistan, pointing to the presence of havens there for militants.

“The terrorists have safe sanctuaries across the border in Afghanistan,” said Anwar-ul Haq Kakar, a spokesman for the Baluchistan government. “They have become a major source of terrorism inside Baluchistan.”

Many minority leaders, however, stressed that there was a bigger need to look inward to ensure security for religious minorities, especially Christians.

“This attack is a serious breach of security,” Mr. Gill said

From Trauma to Inspiration- Three years later APS survivor ready to change the world

Three years after the Army Public School Peshawar attack that claimed life of 144 students, the world might have moved on but not the families and victims of the massacre.

Labelled as the bloodiest attack in the country’s history, it is hard to imagine the struggle of the victims despite moving three years down the memory.

On the night of 15th December 2014, Ahmad Nawaz and his younger brother Haris Nawaz went to bed together, hardly realizing that it would be the last time both of them are sleeping together in a room.

Haris was reluctant to go to school next day but agreed upon his dad, Mohammad Nawaz’s insistence, an agreement that was to haunt Mohammad for years to come.

Haris kept whining all the way to school about how he could have stayed at home and slept.

Ahmed Nawaz, Mohammad Nawaz’s eldest son, aged fifteen at the time, was in the main auditorium of the school, attending a first-aid training session in which they were being taught about how to deal with a calamity in case one happens. It was 10 am and no one had any idea of what may precede.

Mohammad Nawaz was headed toward his car workshop around 10:30 am when he received a phone call informing him about the attack on the school that his two sons had gone to. Not caring much, he continued to go about his daily business, trying to recover from the death of his close relative.

An hour later, he received another phone call which told him about the rising number of casualties being reported from the attack.

Pakistan marks the third anniversary of militant raid on Army Public School

Two of his sons had gone to school that day. He didn’t want to contemplate the options that the situation was presenting to him but pretty soon he was rushing behind the ambulances that were taking injured and dead people from Army Public School to various hospitals in the city.

When the ambulances stopped at one of the hospitals, he started frantically searching for his missing sons.

His phone rang and this time it was his eldest son, Ahmed Nawaz talking to him in a stable voice and telling him of his whereabouts.

Six hours had passed and still no clue was to be found of his second son, Haris Nawaz whom Mohammad had forcefully sent to school in the morning.

His son who was known for having a heart of gold, who would go out of the way to help others and would get stressed when he would see the plight of Muslims abroad, was nowhere to be found.

Mohammad received another call around 4 pm. This time it was his brother asking him whether his younger son wore a watch to school that day.

Surprised, Nawaz checked with his wife who said he didn’t but younger son, Umar Nawaz informed them that he had taken his black watch and worn it to school that day.

The wrist watch became the source through which Haris Nawaz’s mutilated dead body was recognized by his immediate family.

The wrist watch was still clinging on to his chubby wrist when his family found him, as his face was unrecognizable from being blown up with a Kalashnikov.

Hospitals were echoing with crying and screaming mothers, fathers, and relatives of the children whose dead bodies were being brought in by the ambulances.

Body parts belonging to different bodies were scattered everywhere, heads were squished from being blown up by Kalashnikovs.

On December 16, 2014, it was 10 am in the morning and Ahmad and his school mates were gathered in the auditorium where they were being taught about first-aid training.

The first gun shots were heard from near the main hall in the front. Everybody got confused but the training officers assured the students to not worry and continued with the training.

Few minutes later, the door was knocked open by black turban wearing militants who shouted Allah-o-Akbar and opened fire on the hall full of students aged 13 to 16. The otherwise quiet hall turned into a room echoing with gun fires, screams of children, flying furniture and dead bodies falling to the floor.

Ahmad crouched lowest in his seat and tried to make sense of his surroundings. He assumed the situation was part of the first-aid training but the assumption was short-lived when he saw dead bodies falling and blood pouring all around him. Ahmad hid under his chair along with his other friends but their secret was short-lived as the terrorists discovered their hiding place and shouted to each other, “These scums are hiding under their seats. Kill each one of them.”

Ahmad said his last prayers and got ready to embrace death. A man wearing black turban neared the row of chairs under which Ahmad and his friends were hiding and started shooting at the exposed heads and bodies of the children.

Ahmad’s friend was hiding under the chair beside him. The terrorist approached him and fired shots aimed at his head.

Blood, flesh and gunpowder came flying on Ahmad’s face. Now it was Ahmad’s turn to leave the world but as luck had it, Ahmad’s head was hidden under the chair so he received shots in his left arm as the terrorist hurriedly walked by trying to kill ‘every hiding scum’.

The blood pouring from Ahmad’s hand covered his head in a puddle of blood. As soon as the terrorists left, Ahmad along with a few other injured students, who were alive, got up and tried to hide in the dressing room beside the stage.

Ahmad dropped himself at the door of the dressing room as he couldn’t walk any further. The room was full of children and a teacher who were moaning under the excruciating pain of injuries. Just when they thought that the terrorists would not return, they actually did.

This time they not only fired at the injured students but set the little room on fire too. Ahmad who was lying on the floor near the room stayed very still, making no noise and pretending to be dead. The terrorists stepped on him and walked out of the hall.

Ahmad had survived for the second time and was hoping to get rescued before a third encounter and his prayers got answered as he heard the rescue team approaching and hoisted himself up with the remaining energy in his body and reached Lady Reading Hospital in an ambulance full of dead bodies.

A year later admitted in Queen Elizabeth Hospital in Birmingham, England, Ahmad would wake up at night and tell his parents to close all doors and check the cupboards because ‘black turban wearing men are hiding in it with guns

Ahmad had his first longest surgery to save his arm that lasted for sixteen hours in which the veins of his injured arm were stretched and sewn together to enable it to work normally in future.

Laying on his hospital bed under agonizing pain and trying to come to terms with the loss of a younger brother and pain of an operated arm, Ahmad discovered through Television that about 800 children in UK have left for Syria, Libya, and Iraq to join the militants.

This came as disturbing news to the young lad who would still wake up from dreams shouting and crying and asking ‘the men in black to leave him alone.

It was Ahmad’s moment of realisation as he told his father about how he wishes to spread awareness and tell students in UK about how he has been victim of these militants and how they are not connected to Islam in any way. His dad profusely encouraged him.

Soon afterwards, Ahmad was on his way to physical and psychological recovery with the help of a supporting community at his school, family and friends.

Taking inspiration from his traumatic experience, Ahmad took up the campaign of educating UK students about the terrorist militants who were responsible for taking lives of 144 students in the APS school attack.

With the help of Anne Frank Organization, in September 2015 Ahmad started a campaign on education to reach and aware young students in UK about the curse of militants that is, Taliban.

Ahmad shared his story wherever he went and became a source of inspiration for young school children. Ahmad was called-in by British Prime Minister Theresa May, Speaker of House of Lords Mrs. D’Souza and various other ministers and officials in the House of Commons and House of Lords to encourage and acknowledge his bravery and spirit to make the world a better place.

Three years to the horrific event, Ahmad now stands tall and determined as ever to lead the world toward literacy, peace, and acceptance. He is serving as the youth ambassador of World Merit Organisation, and the Anne Frank Organisation. He has been presented the Award of Bravery and Resilience by Government of Pakistan, and UK and Europe young person of the year award.

Having given speeches as key note speaker at United Nations and attended Estoril conference of the Nobel Prize laureates’ fame, Ahmad is on a mission to make the world a peaceful and safe place for future generations so no other child has to watch their friends and teacher get shot and burned alive to death or wake up at night screaming from nightmares of their murderer’s faces

https://www.thenews.com.pk/latest/256898-from-trauma-to-inspiration-three-years-later-aps-survivor-ready-to-change-the-world