It took 15 minutes for my car to creep forward about 20 feet, giving me ample time to admire the crumbling filigreed balconies jutting precariously overhead.

Throughout the gridlocked lanes of Hyderabad’s Old City, mud-splattered ancient ramparts are studded with tea stalls, Western Union signs and makeshift roadside repair shops stacked with washing machines waiting to be coaxed back to life. There are glimpses of glory amid the rubble and grime: a solitary remnant of a once-imposing palace wall peeks out timidly amid a labyrinth of electric wires; latticed windows blackened by generations of soot and rain are further obscured by corrugated tin shacks.

“There’s such beauty, but how pathetically it’s been destroyed,” said Dr. Anand Raj Varma, a local scholar and historian who was accompanying me. “Sab khatam ho gaya. Nothing is there.”

I was raised far from India on my father’s outlandish tales of Hyderabad’s magnificent deoris — sprawling walled estates — and of the city’s fragrant gardens and refined etiquette, stories that were passed down from his own father. He watched that world evaporate from the 1950s through the ’70s, and his anecdotes typically end with him shaking his head in wonder: “You couldn’t fathom it.” He barely can himself.

“Everything’s gone now,” he bemoans, like Dr. Varma. Thanks to a lethal mix of government neglect and citizen apathy, and the financial collapse of the aristocracy after the state was absorbed into India in 1948, much of old Hyderabad has been decimated, giving way to a congested urban abyss. The Hyderabad of my father’s nostalgia seemed as implausible to me as Atlantis.

I mostly ignored his lamentations, as teenagers are wont to do. But as I grew older and sought a deeper connection with the city I consider my second home, I began to wonder how things might have been 60 years ago, before Hyderabad’s gracious boulevards were engulfed by dreary concrete blocks. When my maternal grandfather, Mahmood bin Muhammad, a senior administrator, diplomat and writer, died in late 2013, that mild interest graduated to obsession. Most of the buildings my father speaks of dissolved into oblivion decades ago; the people who recall that era are also ebbing away.

And so I returned to see what was left, before both the physical vestiges and the memories that sustain them are lost forever.

Hyderabad isn’t an easy place to love. Delhi has its historical monuments, Rajasthan its palaces, Kerala its lush backwaters and Mumbai its Bollywood glamour. Hyderabad languishes, suspended between a stifled past and a future not yet fully realized. The week I arrived, a politician was making headlines for claiming that his party did more for the state in nine years than the erstwhile ruling Asaf Jahi dynasty, better known as the Nizams, did in hundreds.

Continue reading the main story

The senior-most princes in India during the British Raj, the dynasty of the Nizams reigned over a state the size of the Britain. The seventh and final ruling Nizam, Mir Osman Ali Khan, was proclaimed the richest man in the world on a 1937 Time cover, with a net worth estimated to amount to more than $35 billion in today’s terms. “He spent his leisure hours dipping his arms up to the elbows in chests of diamonds, emeralds, rubies and pearls,” read his 1967 New York Times obituary. He also bestowed the state with educational institutions, hospitals and infrastructure galore.

But Hyderabad has lately reinvented itself as Cyberabad, home to gleaming offices for Facebook, Google, IBM and Oracle. Last year, the city was abuzz with news that a hometown boy, Satya Nadella, had succeeded Steve Ballmer as chief executive of Microsoft. Technology is king today, eclipsing the endowment of bygone monarchs.

“The Nizam has done so much for Hyderabad, and people forget it very quickly because they have short-term memories,” said Princess Esra Jah, an ex-wife of the seventh Nizam’s heir, Prince Mukarram Jah. I had arrived via horse and carriage at the Falaknuma Palace, a Tudor-Italian marvel reborn in 2010 as a sumptuous Taj hotel, to have tea with the princess responsible for its restoration.

“How can they say he did nothing for Hyderabad if it was the most advanced” princely state in all of India? said the princess. “It’s in the history books. But I don’t think most of the politicians read history, if you ask me.”

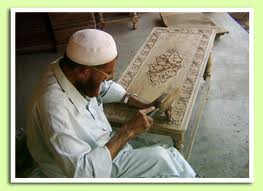

The princess, who looks just as elegant today as she did as a young ingénue in footage from her then-husband’s 1967 coronation, now splits her time among Istanbul, London and Santa Barbara, Calif.; she came back at the prince’s request to return some family properties to their original splendor. “I took on two projects, the Chowmahalla and Falaknuma palaces, to restore them and to be able to give something back to the city,” she said. This was an arduous task; Falaknuma took more than a decade to bring back to its 1890s glory. “It’s very easy to construct, but difficult to restore,” she said.

Indeed, there must be something to restore in the first place. From Notting Hill in London to the Colaba district of Mumbai, there are countless striking examples of urban development that complement a city’s historical fabric. But in a quest for modernization, much of Hyderabad’s architectural legacy was dismantled, and recent attempts to revisit the past are often a case of too little, too late. “Right from the beginning, people did not give enough importance to restoration,” the princess said. “Buildings came up with no aesthetic sense at all. Just because you are high-tech, it doesn’t mean you have to be ugly.”

Continue reading the main story

High atop a hill, Falaknuma stood empty for decades, shrouded in cobwebs and awaiting its moment. The wonder of Falaknuma isn’t just in the Taj’s immaculate re-creation of the palace’s rooms and gardens, though its 101-seat dining table, stained-glass terrace dome and refreshed frescoes are indeed impressive. The magic lies in its simultaneous re-creation of a lost era of refined manners, or tehzeeb.

My family are among the few people I know who still greet their elders with the traditional “aadaab,” raising an upturned palm to the forehead while bowing slightly at the waist. But murmurs of “aadaab” reverberate throughout Falaknuma’s halls, with everyone from the general manager to the gardeners calling out to me as I pass.

“The manners were wonderful,” said Princess Esra Jah of what she loved most about the Hyderabad of old. “It wasn’t just the nobility or the rich or the poor; everyone had the same manners. They were terribly dignified in their behavior.” The Taj team may set out to revive an edifice, but the nostalgic sense of social grace rekindled at the same time is priceless.

A few days later Dr. Varma and I crossed the Musi River, flanked by the bulbous domes of the High Court and the Osmania General Hospital, and the car lurched us into the maze of the Old City. We did a circuit past monuments like the iconic 1591 Charminar arch and the sprawling 17th-century Mecca Masjid mosque before arriving at a bright yellow gate. Behind it lay Purani Haveli, the sixth Nizam’s palace, a lavish spread famed for its legendary 262-foot closet — a necessary amenity for a man who reportedly never repeated an outfit. These days, parts of the property are home to a museum and an engineering college, while the rest of its wilting cupolas and turrets lie derelict.

A caretaker eyed us quizzically as we approached. “I just want to show her around,” Dr. Varma said, and the guard waved us in without further questioning. We roamed freely, peering behind a faded curtain rippling in a doorway to find broken windows, dilapidated fountains and jaundiced plasterwork. Hyderabadis are famously laid-back but also unfailingly hospitable, and this combination worked in my favor; “mulahiza,” or gracious deference, defined most of my interactions. All you have to do is ask, I learned quickly: a smile, a polite entreaty, and warm welcomes ensued.

Over the next week, simply by asking nicely, I gained entree to residences, ruins, private clubs, colleges and palaces. I was tipped off to the 17th-century Goshamahal Baradari, an imposing Masonic temple where, despite the fact that I claimed no allegiance to the Freemasons, I was led through inner chambers clearly labeled “Members Only.” At the Hussaini Kothi deori, a family hosted me in their 200-year-old living room, brimming with colorful antique chandeliers and furnishings in impeccable condition. I visited family friends at the neo-Classical Aziz Bagh, where seven generations have lived since 1899 in a three-acre compound so bucolic you’d never guess it existed deep within the thrum of the Old City. At Famous Ice Cream, a city institution embedded in the 1935 Moazzamjahi Market complex, I stopped for dessert and poked around the sepia-tinted stone arcade.

Continue reading the main story Continue reading the main story

Continue reading the main story

Directly opposite a gaudy sari shop near the chaotic Begum Bazaar, I visited the fashion designer Vinita Pittie at her 250-year-old mansion, a legacy of her husband’s forefathers ( financiers to Hyderabadi nobility) that she has taken great pains to preserve. Vibrant tones of scarlet and emerald dominate her immaculately maintained living room, and delicate chandeliers sway from weathered hand-painted ceilings. Over a cup of decadent saffron tea, she told me why leaving the traffic-clogged arteries to escape for a more modern abode in the new city was not an option. “This house is an entity that has a soul. Just like humans, it too has a destiny — so the question of leaving it doesn’t arise,” Ms. Pittie told me. “People ask how long we’ll stay. I say, ‘Let’s see how long this haveli keeps me,’ ” she said of the house.

Osmania University College for Women teems with students dawdling amid a mishmash of forgettable buildings. But one stands out: In the heart of the campus, two stone lions stand sentinel by a Palladian structure reminiscent of the Pantheon, complete with six imposing Corinthian columns. I approached a group of girls sitting astride one of the lions, gossiping away under the pretext of reviewing notes. “Excuse me, what building is this?” I asked. They shrugged, uninterested in what’s quite literally under their noses. I retreated down the steps, many years’ accumulation of dried bird excrement crunching beneath my feet, to seek anyone who might give me access.

Readers of William Dalrymple’s historical “White Mughals” are familiar with the building I had sought out this afternoon. In his impeccably researched biography, Mr. Dalrymple chronicles the love affair between the British Lt. Col. James Achilles Kirkpatrick and his Muslim bride, Khair un-Nissa, which played out here at the erstwhile British Residency in the early 19th century. After being converted into a college in 1949 — my grandmother and mother both studied there, and have fond memories of eating their lunches on the cannons stationed out in front — the building fell into tatters. These days it lies neglected despite the constant activity surrounding it, waiting for a much-needed restoration courtesy of a World Monuments Fund grant to begin.

As I circled the dilapidated structure, stepping over waist-high weeds and puddles of leaking water, I finally encountered a professor who pointed me in the direction of the administration building, where I could ask for permission to access the Residency. After a brief audience, the principal smiled and gave me her blessing, and sent a caretaker to accompany me inside. He released the flimsy padlock and pushed open the doors, revealing two grand staircases that curve to fuse into a magnificent egg-shaped atrium. Despite the pockmarked walls branded by scores of students inscribing their names over the years, despite the stray birds soaring in and out of broken windows, despite the carcass of a chandelier hanging limply overhead, I was mesmerized. I had entered a time capsule abandoned in plain sight.

The late afternoon sun filtered a honeyed aura over the contours of the massive dome, casting me into my own celluloid vision: Lavish parties and imperial intrigue played out all around me. I could picture the grandeur that was Hyderabad. At long last, I’d found Atlantis.