There was palpable excitement among students crowding 137 Hasbrouck at University of Massachusetts Amherst — the classroom designated to me to teach “Gender Politics and Mass Media in Muslim World” this past spring. It was a course I had designed after Sept. 11 to cater to the tremendous interest generated in Islam and the region I’d taught about at Amherst College a year ago — Iran, Pakistan and Afghanistan.

Students from more than a dozen departments at UMass enrolled in my course — offered through Women Studies and cross-listed with journalism. Apparently my own background as a journalist from Pakistan had attracted many — including a handful of males — interested in root causes of terrorism. Women, already interested in the gender politics of the Muslim world, now enrolled to study these countries from a global perspective.

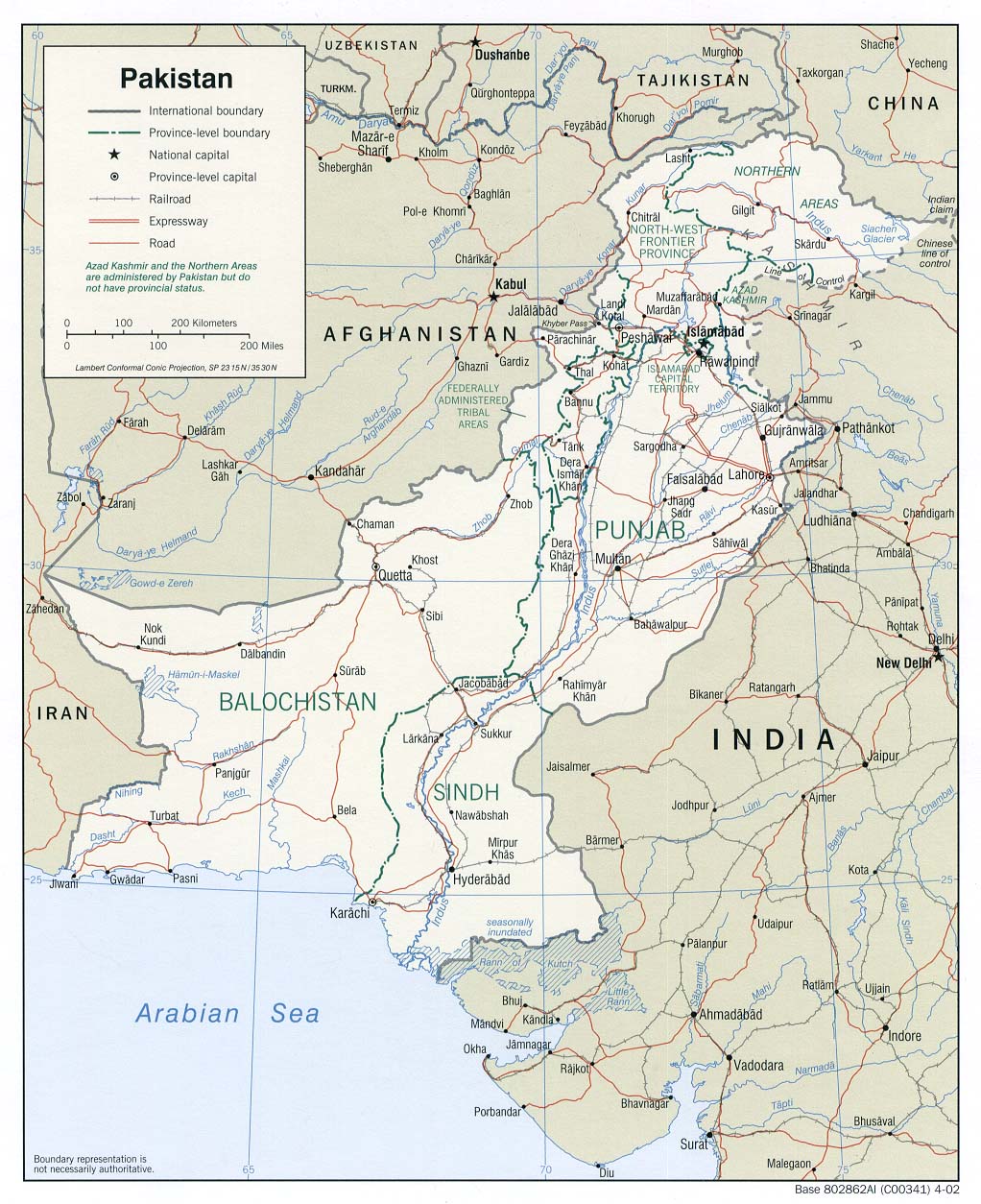

Among those who arrived for the course — young, white and working class — many had grown up on a steady diet of television entertainment news. Lately, television was throwing out names that were difficult to pronounce: Tally Ban, Af-Gan-is-Tan, Pak-is-Tan. They stared at the world map, unable to locate the countries. Why had I expected anything different? Not long ago, presidential hopeful George W. Bush, when quizzed about the Taliban, had asked, “Are they a pop group?”

Apparently, a few were looking for ready-made answers. They appeared bewildered as I began my lecture from 6th century A.D. — about a foreign religion with foreign believers. In my opening lectures about the rise of Islam and the Caliphate, an exasperated young woman at the back of the room yelled: “What does that have to do with 9/11?” My answer was “Everything.”

I let on quite early in the course that in order to understand Islamic fundamentalists, one needed to study the rise of Islam. While the industrial revolution has catapulted the West into the 21st century, traditional Islamic societies — with their tribal and feudal structures — are still deeply influenced by Islamic and pre-Islamic values.

For the majority of students who stayed on, we journeyed to understand Islam. Fatima Mernissi’s book, “The Veil and the Male Elite,” would lay out the historical conditions of 627 A.D. when Prophet Mohammed issued Q’uranic injunctions like the veiling of women — “splitting the Muslim space.” Under colonial rule, the Islamic bloc would experience only superficial modernization. Leila Ahmed’s book, “Women and Gender in Islam,” and Deniz Kandiyoti’s “Introduction to Women, Islam and the State” would provide valuable insight into how 20th-century colonialists used the low position of women in Islamic countries to put down foreign cultures — contributing to the rise of Islamic fundamentalism.

My course would cover the revival of Islamism by the regimes that seized power in Pakistan (1977), Iran (1979) and Afghanistan (1992) . The political use of Islam grew toward the end of the Cold War when the West supplied billions of dollars worth of arms to Pakistan to assist Afghan Mujahideen and mobilize Islamists from around the world to drive the Soviets out of Afghanistan. This was the embryo of the Al Qaeda network — which has today come back to haunt the United States.

There was special interest in my five-week series of lectures on the United States and the regional media’s coverage of 9/11. Having recently returned from a fact-finding survey of the media in Islamabad, Peshawar and Quetta, Pakistan, I was able to update students on the regional media’s reaction to Sept. 11.

On their part, the students combed the internet for the U.S. media’s response to 9/11 — creating an interesting juxtaposition between the two. We had interesting discussions on current topics. While I condemned Palestinian suicide bombings of civilians, students put down Israeli expansionism. They were most critical of the U.S. for spending billions of dollars to bomb Afghanistan while giving a pittance for reconstruction.

“If we, as college students can understand that this is only going to breed terrorism, why can’t the State Department understand that?” a student was asking.

Since my course title covered so many topics — being as one put it “three to four courses rolled in one” — I gave my class the option of writing about their topic of interest. For those who did well in the first short paper, I was careful not to inflate their mid-term grades. This strategy appears to have worked well — allowing 17 students (about half the class) to secure A’s or AB’s on their final papers. Although student evaluations suggest they struggled to keep up with the readings, there were many appreciative comments.

“This is the best course I’ve taken in three years,” was one. A few stayed back after the final class to thank me. “This is a wonderful course, I’ve learned so much,” one woman — a journalism major — told me. For me, the student feedback — conveyed orally, e-mailed or written on paper — made the teaching worth while.

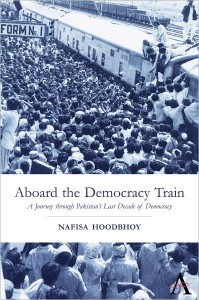

Nafisa Hoodbhoy taught at the University of Massachusetts Amherst this spring. She was a staff reporter for the Dawn newspaper in Karachi, Pakistan, from 1984 to 2000 and is writing a book on the last 20 years of Pakistan’s politics.

Source: India New England