WESTFIELD, Mass. – A group of women from India and Pakistan who came here for a peace conference in April returned home to find their countries on the brink of a nuclear catastrophe. One of the delegates wrote back to me about the “horrific atmosphere of war,” which can be averted, she said, only through “sheer good luck.”

Luck, of course, plays a magnified role in the lives of many on the subcontinent who cannot rely on receiving the staples that most Westerners take for granted. But sheer chance is not what anybody wants to think is the only thing between rice-for-lunch-as-usual and a nuclear conflagration that U.S. experts estimate could kill as many as 12 million people.

Yet that is what the escalating political rhetoric has made women like these believe — that the tensions, the saber-rattling, the missile tests and the brutal deaths on either side of the Line of Control in predominantly Muslim Kashmir have less to do with the hopes of the ordinary people than with the self-serving and mercurial goals of their leaders. With a leader like President Gen. Pervez Musharraf, who came to power in 1999 in a military coup, Pakistanis fear all the more that their country’s response will be a military one. How ironic it was, one Indian delegate pointed out during the conference, that with flights and overland travel between their countries cut off, these women had to travel to the United States — more than 7,000 miles away from home — in order to meet face to face with their counterparts.

The delegates had gathered at the conference, titled “Women of Pakistan and India: Rights, Ecology, Economy and Nuclear Disarmament,” at Westfield State College just as the war clouds were forming over the subcontinent. Tensions had been building since January, when India accused Pakistan of supporting the Kashmiri militants’ attacks on its parliament in Dehli on Dec. 13 — and retaliated by massing its troops on the border. The potential for a nuclear exchange has since been triggered by the Islamic militants’ attack on an army camp in mid-May. The raid killed more than 30 soldiers and family members. That’s when Indian Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee rallied troops for an all-out war. In a show of defiance, Pakistan tested three missiles last week (all of them named after Muslim conquerors of India) that are capable of launching a nuclear attack on the Indians. The United States is taking all of this seriously, urging Americans to get out of India and withdrawing all but essential embassy personnel.

For the 10 women from India and Pakistan, coming to Westfield was an occasion to analyze how governments on each side had hijacked discourse to portray the other as the “enemy.” Growing up in Pakistan, I was a witness to the constant hammering by state-controlled television about “Indian atrocities in occupied Kashmir.” In fact, the phrase masla-i-Kashmir (“the problem of Kashmir”) has for me become a metaphor for any problem that can never be solved.

I heard those thoughts echoed in the views of the Indian women at the conference. Journalist Kalpana Sharma blamed her nation’s worsening relations with Muslims, and by association with Pakistan, on the rise of the Hindu fundamentalists in India — the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and its coalition partner, the Vishwa Hindu Parishad (VHP). India, Sharma said, had buckled under fundamentalist pressure and escalated its military budget after the disastrous conflict near the Kargil area of Kashmir that nearly led to war in 1999. And the costs for ordinary people are clear. India has cut back on the social sector, she said, and instituted higher taxes on its people.

For Anis Haroon, director of a women’s non-governmental organization in Karachi, the U.S. support for Musharraf after Sept. 11 “had carved out a permanent role for the army in Pakistan.” This, she said, had come with costs, strengthening the military crackdown on demonstrations by political parties, civil liberties groups and women protesting against discriminatory laws. In early May, for example, Pakistani authorities arrested women gathering to oppose the Hudood Ordinances, which demonstrators say end up punishing female victims of rape.

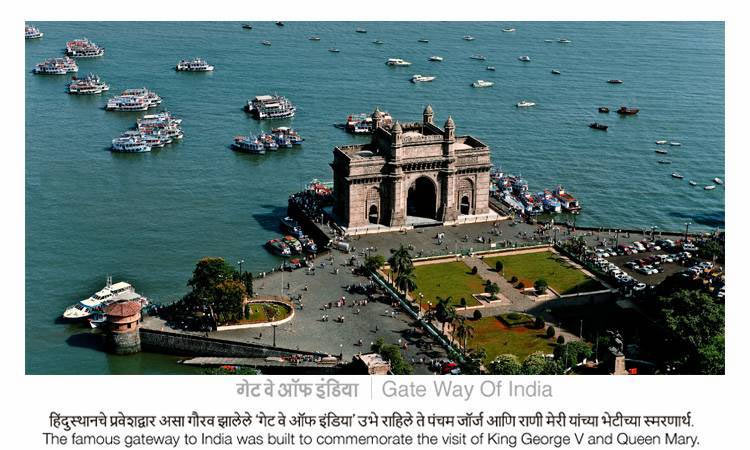

Civil liberties have taken a beating inside India as well, agreed the Indian women. Ruchira Gupta, a member of a women’s group in Bombay, pointed to the Indian parliament’s passage of the Prevention of Terrorism Act (POTA) on March 26 as an example. POTA was advocated by BJP Home Minister L.K. Advani to counter what he called “the terrorism” launched by Pakistan. But Gupta argued that the act would cramp the press, militarize the society and lead to injustices for Muslim minorities.

Both governments, these women believed, were responsible for recent atrocities. The Indians blamed the massacre of Muslims in Gujarat in February following an attack on Hindus in a train on the “frenzy whipped up by the BJP” which forms the central government in Gujarat. The Hindu delegates said that organizations they belonged to had visited the area to distribute food and clothing to Muslim victims. Correspondingly, Pakistani delegates said that the Gujarat violence had not resulted in reprisals against Hindus in Pakistan — showing that such violence is not supported by ordinary people.

Indeed, my experience shows that all too often it is the self-serving leaderships in the two countries that thwart the people’s desire for peace. I saw this firsthand in 1995. As a journalist, I was invited to join the official Pakistan delegation to the Fourth World Women Conference in Beijing. The country was then ruled by Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto, who was keen to portray a liberal image at the conference. But we were instructed by a male leader of our group to counter the Indian delegates each time the subject of Kashmir came up. I watched as the leaders of both the Indian and Pakistani delegations engaged in allegations and counter-allegations over Kashmir. Slowly the hall began emptying as U.N. delegates walked out of a meeting that was supposed to unite the women of the world.

The discussions at Westfield did not fracture along these lines because the women were not here to promulgate their governments’ policies. Instead, they discussed how Sept. 11 has caused India and Pakistan to vie for U.S. attention over Kashmir. Even as India conducts its propaganda war against militants, it stopped Kashmiri women from attending our conference. The pressure was coming from the Hindu right wing, who, as Indian delegate Urvashi Batalia noted, had been cashing in on the “demonizing of Muslims.”

U.S. dependence on Pakistan in its fight against terrorism appears to have given legitimacy to the military government, argued Zubeida Mustafa, a senior editor from Pakistan’s daily Dawn newspaper. In Pakistan’s April referendum, journalists observed few voters at the polling booths. A colleague wrotethat a polling officer he visited had recorded only 125 votes by closing time. The officer told him rather casually that he forged the remaining votes after deadline because the local police directed him to show a voter turnout of nearly 900 and to ensure a “yes” vote of around 98 percent, giving Musharraf five more years in office.

With only the facade of being elected, Pakistan’s military government has not had to answer to its people about the failure to improve law and order. Earlier this year, targeted killings of Shia doctors by Sunni extremist groups forced physicians to flee the country. However, no action was taken until last month, when a suicide bomber killed 14 people in Karachi, including 11 French men working on a submarine project. Under severe international pressure, the Musharraf government cracked down on the Sunni militant groupLashkar-i-Jhangvi — which has been linked to the killings of Shia doctors. Later, three members of this same group were accused in the brutal murder of American journalist Daniel Pearl.

In December, when I last visited Pakistan, I was curious to see how the Musharraf government would rein in Kashmiri militants. The Islamic militants who were brought into the region by the United States during the Cold War had turned to jihad in Kashmir after the Soviets withdrew from Afghanistan in 1989. Since then about two dozen militant Islamic groups fighting for Kashmir under the United Jihad Council have established headquarters in Pakistan.

It’s not as if Kashmiris welcome such support. One Kashmiri from Srinagar, Farooq Lone, who now lives in Islamabad, told me that Kashmiris are “fed up” with Pakistan-based militants who attack Indian forces and leave the Kashmiris to face the vengeance of the repressive Indian troops. More than 35,000 people have been killed in Kashmir since the militants entered the fray 13 years ago. Lone’s family supports the All Parties Hurriyet Conference, whose moderate Kashmiri separatist leader, Abdul Ghani Lone, was recently assassinated. Although India has never allowed a plebiscite in which the Kashmiris could decide their own fate, the Indian government had been wooing moderates such as Lone for elections planned in Kashmir in September. His murder deals a further blow to any peace prospects. And it is a further example of the voice of the people being stifled.

The issue of Kashmir — left dangling by the British in 1947 when they divided India and then departed without forcing a plebiscite — has come to haunt the United States almost 55 years later. It is an issue that is not going be resolved by luck or through a U.S. admonition to Pakistan to stop abetting militants. Instead, the United States will have to throw its weight behind the United Nations to enable the people of Kashmir to decide their own fate. That appears to be the only choice if the world is to be successful in fighting the roots of terrorism.

Source: Washington Post