(Credit: theguardian.com)

London, June 3: On Tuesday, police in London arrested a man on suspicion of money laundering. Thousands of miles away in Karachi, Pakistan’s turbulent coastal metropolis, traffic snarled, shops shuttered, trains stopped, embassies closed and millions braced for further havoc. (As of Tuesday evening, there were reports of gunfire and 12 vehicles set aflame, but no casualties.)

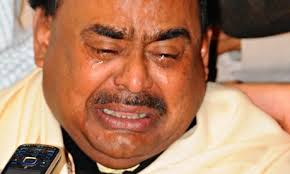

The man taken in by Scotland Yard is Altaf Hussain, leader of Muttahida Qaumi Movement (MQM), the dominant political party in Karachi. Despite living in self-imposed exile in Britain for more than two decades out of fear for his life, Hussain has remained a kingpin in this megacity of nearly 20 million, depending on how you count it. He casts a long, dark shadow over the city, notorious for its gangland violence and volatile political divisions.

The MQM draws support from Karachi’s large population of mohajirs, the descendants of those who migrated to Pakistan from what is now India in 1947, when colonial India was cleaved in two by the departing British. The party commands a crucial bloc of seats in Parliament, almost all of which are concentrated around Karachi in southern Sindh province.

The city’s ethnic polarization — it’s also home to huge ethnic Pashtun and Sindhi populations — has led to years of sectarian tensions, punctuated by attacks and street battles. The MQM’s vast political machinery is complemented by brass knuckles. A leaked 2008 U.S. diplomatic cable, citing local police, claimed that the party maintained its own parallel militia of as many as 10,000 active fighters, with 25,000 in reserve.

British authorities have been investigating Hussain, 60, since the 2010 assassination in London of a MQM official, Imran Farooq, who had grown estranged from the party. Last week, they froze Hussain’s bank accounts. MQM officials said today that he was brought in only for questioning, but it seems clear that he is under arrest.

Hussain is considered a charismatic, larger-than-life figure. Ensconced in his compound in northwest London, he would coordinate the operations of his party via teleconference and get beamed over satellite to address mass gatherings and rallies.

While the MQM has staunch middle-class backing and is credited with running Karachi efficiently, it is thought to benefit from a whole slew of underworld activities, including extortion and targeted attacks on opponents. MQM officials routinely deny any connection to such wrongdoing.

Hussain himself has earned notoriety for his incendiary rhetoric — once telling an aggressive journalist that he had “his body bag ready” and, in another instance, warning critics to end their “false allegations” against him. “Don’t blame me, Altaf Hussain, or the MQM,” he said, “if you get killed by any of my millions of supporters.”

Scotland Yard may struggle to charge him with incitement to violence or prove a direct link to Farooq’s death. So it appears its most solid case surrounds Hussain’s funds and their use in Britain. Earlier raids on Hussain’s house led to the impounding of about $600,000 in cash.

Meanwhile, in Karachi, MQM officials have called for calm, sending out mass text messages throughout the city advising residents to ignore rumors that could cause further disruption or violence. Like many political parties in South Asia, the MQM’s cohesion depends greatly upon the presence of its towering founding figure. The doubts and fears in Karachi are as much about what happens at home as they are about what happens in a British courtroom far away