The driving force behind the campaign against her has been the Jamaat-i-Islami (JI). On March 28, 2015, its student wing the Islami Jamiat-i-Talaba (IJT) organised a multiparty conference on curriculum change. JI’s Sindh emir, Dr Meraj-ul-Huda Siddiqui, declared as “intolerable” the Sindh advisory committee’s efforts to remove mandatory religious lessons from general knowledge, Sindhi, Urdu and Pakistan Studies textbooks

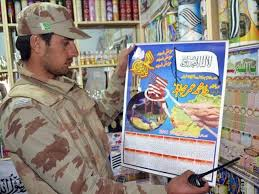

Singling out the only non-Muslim member of the committee, the JI and IJT launched a personal attack on Dr Dean. Karachi was plastered with inflammatory banners targeting her. She was accused of being “a foreigner woman who has single-handedly made changes to the curriculum and textbooks that made them secular” and called an enemy of Islam. The truth is that she was targeted for trying to ensure that school textbooks meet the requirements of the Pakistani Constitution.

Empowered by the 18th Amendment, the Sindh government set up an expert advisory committee in October 2013 to reform the existing school curricula. The committee was mandated to review “the curriculum of primary schools, from class one to five, in order to identify the missing links, gaps and concepts in it … While proposing changes in curriculum the committee will also point out the duplication, overlapping, repetition, bias and other negative values affecting the learning, growth and worldview of the students”.

It was inevitable that in reviewing the curriculum, the committee would confront the fact that the National Curriculum 2006 and public school textbooks based on it clearly violate Article 22(1) of the Constitution. This article says: “No person attending any educational institution shall be required to receive religious instructions, or take part in any religious ceremony, or attend religious worship, if such instruction, ceremony or worship relates to a religion other than his own.”

Article 22(1) of the Constitution clearly means that teaching any particular faith as part of the curriculum must be restricted to students of that faith and such teaching must not be imposed on students of other faiths. It is a simple protection of religious freedom. In practice, this means that the teaching of Islam should be confined to Islamiat classes and textbooks, and should be studied only by Muslim students. Islamic teachings should not be included in classes and textbooks on Urdu, English, social studies, etc which are used by all students, including children from non-Muslim families.

Despite the constitutional obligation, the National Curriculum 2006 required children of all faiths from classes one to three to be taught to “recite and memorise Kalima Tayyaba with its meaning”, and “memorise and recite Darood Sharif with translation” and “memorise and recite prayers for starting and ending fasts in Ramzan”.

Then there are outright expressions of hate against people of other faiths in parts of the curriculum and textbooks covering independence and partition.

The advisory committee was performing its task according to the terms of reference it received. It was trying to purge the curriculum and textbooks of this kind of material. Dr Dean explained that the new textbooks which tried to be consistent with the Constitution had Muslim authors and that she was only a co-author. She also explained that all the books were reviewed multiple times before being approved by the authorities. Regardless, the Sindh government did not come to her defence.

It is not just in Sindh that Islamist parties and activists and their supporters are trying to protect an intolerant national curriculum that violates the Constitution. In Punjab, textbooks written and approved in the past few years continue to violate Article 22(1). In KP, the JI has allied with the Pakistan Tehreek-i-Insaf government to reverse reforms in textbooks that had been initiated by the previous Awami National Party government.

Thirty years ago, in 1985, Pervez Hoodbhoy and I had written an essay Rewriting the History of Pakistan in which we argued that Gen Zia and his political ally the JI “view education as an important means of creating an Islamised society” and that this effort included “the revision of conventional subjects to emphasise Islamic values”. We had warned then, “the full impact … will probably be felt by the turn of the century, when the present generation of schoolchildren attains maturity”. The religious violence the country is now suffering, directed especially at religious minorities, is one result. Without urgent fundamental reform of our education system, this terrible war may last at least another generation.

The writer is a retired physicist who taught at Quaid-i-Azam University and LUMS.