Less than 24 hours later, a missile tore through the compound, severing Mr. Muhammad’s left leg and killing him and several others, including two boys, ages 10 and 16. A Pakistani military spokesman was quick to claim responsibility for the attack, saying that Pakistani forces had fired at the compound.

That was a lie.

Mr. Muhammad and his followers had been killed by the C.I.A., the first time it had deployed a Predator drone in Pakistan to carry out a “targeted killing.” The target was not a top operative of Al Qaeda, but a Pakistani ally of the Taliban who led a tribal rebellion and was marked by Pakistan as an enemy of the state. In a secret deal, the C.I.A. had agreed to kill him in exchange for access to airspace it had long sought so it could use drones to hunt down its own enemies.

That back-room bargain, described in detail for the first time in interviews with more than a dozen officials in Pakistan and the United States, is critical to understanding the origins of a covert drone war that began under the Bush administration, was embraced and expanded by President Obama, and is now the subject of fierce debate. The deal, a month after a blistering internal report about abuses in the C.I.A.’s network of secret prisons, paved the way for the C.I.A. to change its focus from capturing terrorists to killing them, and helped transform an agency that began as a cold war espionage service into a paramilitary organization.

The C.I.A. has since conducted hundreds of drone strikes in Pakistan that have killed thousands of people, Pakistanis and Arabs, militants and civilians alike. While it was not the first country where the United States used drones, it became the laboratory for the targeted killing operations that have come to define a new American way of fighting, blurring the line between soldiers and spies and short-circuiting the normal mechanisms by which the United States as a nation goes to war.

Neither American nor Pakistani officials have ever publicly acknowledged what really happened to Mr. Muhammad — details of the strike that killed him, along with those of other secret strikes, are still hidden in classified government databases. But in recent months, calls for transparency from members of Congress and critics on both the right and left have put pressure on Mr. Obama and his new C.I.A. director, John O. Brennan, to offer a fuller explanation of the goals and operation of the drone program, and of the agency’s role.

Mr. Brennan, who began his career at the C.I.A. and over the past four years oversaw an escalation of drone strikes from his office at the White House, has signaled that he hopes to return the agency to its traditional role of intelligence collection and analysis. But with a generation of C.I.A. officers now fully engaged in a new mission, it is an effort that could take years.

Today, even some of the people who were present at the creation of the drone program think the agency should have long given up targeted killings.

Ross Newland, who was a senior official at the C.I.A.’s headquarters in Langley, Va., when the agency was given the authority to kill Qaeda operatives, says he thinks that the agency had grown too comfortable with remote-control killing, and that drones have turned the C.I.A. into the villain in countries like Pakistan, where it should be nurturing relationships in order to gather intelligence.

As he puts it, “This is just not an intelligence mission.”

From Car Thief to Militant

By 2004, Mr. Muhammad had become the undisputed star of the tribal areas, the fierce mountain lands populated by the Wazirs, Mehsuds and other Pashtun tribes who for decades had lived independent of the writ of the central government in Islamabad. A brash member of the Wazir tribe, Mr. Muhammad had raised an army to fight government troops and had forced the government into negotiations. He saw no cause for loyalty to the Directorate of Inter-Services Intelligence, the Pakistani military spy service that had given an earlier generation of Pashtuns support during the war against the Soviets.

Many Pakistanis in the tribal areas viewed with disdain the alliance that President Pervez Musharraf had forged with the United States after the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks. They regarded the Pakistani military that had entered the tribal areas as no different from the Americans — who they believed had begun a war of aggression in Afghanistan, just as the Soviets had years earlier.

Born near Wana, the bustling market hub of South Waziristan, Mr. Muhammad spent his adolescent years as a petty car thief and shopkeeper in the city’s bazaar. He found his calling in 1993, around the age of 18, when he was recruited to fight with the Taliban in Afghanistan, and rose quickly through the group’s military hierarchy. He cut a striking figure on the battlefield with his long face and flowing jet black hair.

When the Americans invaded Afghanistan in 2001, he seized an opportunity to host the Arab and Chechen fighters from Al Qaeda who crossed into Pakistan to escape the American bombing.

For Mr. Muhammad, it was partly a way to make money, but he also saw another use for the arriving fighters. With their help, over the next two years he launched a string of attacks on Pakistani military installations and on American firebases in Afghanistan.

C.I.A. officers in Islamabad urged Pakistani spies to lean on the Waziri tribesman to hand over the foreign fighters, but under Pashtun tribal customs that would be treachery. Reluctantly, Mr. Musharraf ordered his troops into the forbidding mountains to deliver rough justice to Mr. Muhammad and his fighters, hoping the operation might put a stop to the attacks on Pakistani soil, including two attempts on his life in December 2003.

But it was only the beginning. In March 2004, Pakistani helicopter gunships and artillery pounded Wana and its surrounding villages. Government troops shelled pickup trucks that were carrying civilians away from the fighting and destroyed the compounds of tribesmen suspected of harboring foreign fighters. The Pakistani commander declared the operation an unqualified success, but for Islamabad, it had not been worth the cost in casualties.

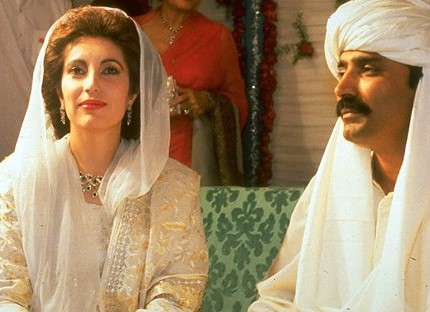

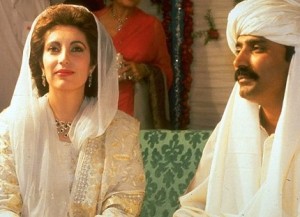

A cease-fire was negotiated in April during a hastily arranged meeting in South Waziristan, during which a senior Pakistani commander hung a garland of bright flowers around Mr. Muhammad’s neck. The two men sat together and sipped tea as photographers and television cameras recorded the event.

Both sides spoke of peace, but there was little doubt who was negotiating from strength. Mr. Muhammad would later brag that the government had agreed to meet inside a religious madrasa rather than in a public location where tribal meetings are traditionally held. “I did not go to them; they came to my place,” he said. “That should make it clear who surrendered to whom.”

The peace arrangement propelled Mr. Muhammad to new fame, and the truce was soon exposed as a sham. He resumed attacks against Pakistani troops, and Mr. Musharraf ordered his army back on the offensive in South Waziristan.

Pakistani officials had, for several years, balked at the idea of allowing armed C.I.A. Predators to roam their skies. They considered drone flights a violation of sovereignty, and worried that they would invite further criticism of Mr. Musharraf as being Washington’s lackey. But Mr. Muhammad’s rise to power forced them to reconsider.

The C.I.A. had been monitoring the rise of Mr. Muhammad, but officials considered him to be more Pakistan’s problem than America’s. In Washington, officials were watching with growing alarm the gathering of Qaeda operatives in the tribal areas, and George J. Tenet, the C.I.A. director, authorized officers in the agency’s Islamabad station to push Pakistani officials to allow armed drones. Negotiations were handled primarily by the Islamabad station.

As the battles raged in South Waziristan, the station chief in Islamabad paid a visit to Gen. Ehsan ul Haq, the ISI chief, and made an offer: If the C.I.A. killed Mr. Muhammad, would the ISI allow regular armed drone flights over the tribal areas?

In secret negotiations, the terms of the bargain were set. Pakistani intelligence officials insisted that they be allowed to approve each drone strike, giving them tight control over the list of targets. And they insisted that drones fly only in narrow parts of the tribal areas — ensuring that they would not venture where Islamabad did not want the Americans going: Pakistan’s nuclear facilities, and the mountain camps where Kashmiri militants were trained for attacks in India.

The ISI and the C.I.A. agreed that all drone flights in Pakistan would operate under the C.I.A.’s covert action authority — meaning that the United States would never acknowledge the missile strikes and that Pakistan would either take credit for the individual killings or remain silent.

Mr. Musharraf did not think that it would be difficult to keep up the ruse. As he told one C.I.A. officer: “In Pakistan, things fall out of the sky all the time.”

A New Direction

As the negotiations were taking place, the C.I.A.’s inspector general, John L. Helgerson, had just finished a searing report about the abuse of detainees in the C.I.A.’s secret prisons. The report kicked out the foundation upon which the C.I.A. detention and interrogation program had rested. It was perhaps the single most important reason for the C.I.A.’s shift from capturing to killing terrorism suspects.

The greatest impact of Mr. Helgerson’s report was felt at the C.I.A.’s Counterterrorism Center, or CTC, which was at the vanguard of the agency’s global antiterrorism operation. The center had focused on capturing Qaeda operatives; questioning them in C.I.A. jails or outsourcing interrogations to the spy services of Pakistan, Jordan, Egypt and other nations; and then using the information to hunt more terrorism suspects.

Mr. Helgerson raised questions about whether C.I.A. officers might face criminal prosecution for the interrogations carried out in the secret prisons, and he suggested that interrogation methods like waterboarding, sleep deprivation and the exploiting of the phobias of prisoners — like confining them in a small box with live bugs — violated the United Nations Convention Against Torture.

“The agency faces potentially serious long-term political and legal challenges as a result of the CTC detention and interrogation program,” the report concluded, given the brutality of the interrogation techniques and the “inability of the U.S. government to decide what it will ultimately do with the terrorists detained by the agency.”

The report was the beginning of the end for the program. The prisons would stay open for several more years, and new detainees were occasionally picked up and taken to secret sites, but at Langley, senior C.I.A. officers began looking for an endgame to the prison program. One C.I.A. operative told Mr. Helgerson’s team that officers from the agency might one day wind up on a “wanted list” and be tried for war crimes in an international court.

The ground had shifted, and counterterrorism officials began to rethink the strategy for the secret war. Armed drones, and targeted killings in general, offered a new direction. Killing by remote control was the antithesis of the dirty, intimate work of interrogation. Targeted killings were cheered by Republicans and Democrats alike, and using drones flown by pilots who were stationed thousands of miles away made the whole strategy seem risk-free.

Before long the C.I.A. would go from being the long-term jailer of America’s enemies to a military organization that erased them.

Not long before, the agency had been deeply ambivalent about drone warfare.

The Predator had been considered a blunt and unsophisticated killing tool, and many at the C.I.A. were glad that the agency had gotten out of the assassination business long ago. Three years before Mr. Muhammad’s death, and one year before the C.I.A. carried out its first targeted killing outside a war zone — in Yemen in 2002 — a debate raged over the legality and morality of using drones to kill suspected terrorists.

A new generation of C.I.A. officers had ascended to leadership positions, having joined the agency after the 1975 Congressional committee led by Senator Frank Church, Democrat of Idaho, which revealed extensive C.I.A. plots to kill foreign leaders, and President Gerald Ford’s subsequent ban on assassinations. The rise to power of this post-Church generation had a direct impact on the type of clandestine operations the C.I.A. chose to conduct.

The debate pitted a group of senior officers at the Counterterrorism Center against James L. Pavitt, the head of the C.I.A.’s clandestine service, and others who worried about the repercussions of the agency’s getting back into assassinations. Mr. Tenet told the 9/11 commission that he was not sure that a spy agency should be flying armed drones.

John E. McLaughlin, then the C.I.A.’s deputy director, who the 9/11 commission reported had raised concerns about the C.I.A.’s being in charge of the Predator, said: “You can’t underestimate the cultural change that comes with gaining lethal authority.

“When people say to me, ‘It’s not a big deal,’ ” he said, “I say to them, ‘Have you ever killed anyone?’

“It is a big deal. You start thinking about things differently,” he added. But after the Sept. 11 attacks, these concerns about the use of the C.I.A. to kill were quickly swept side.

The Account at the Time

After Mr. Muhammad was killed, his dirt grave in South Waziristan became a site of pilgrimage. A Pakistani journalist, Zahid Hussain, visited it days after the drone strike and saw a makeshift sign displayed on the grave: “He lived and died like a true Pashtun.”

Maj. Gen. Shaukat Sultan, Pakistan’s top military spokesman, told reporters at the time that “Al Qaeda facilitator” Nek Muhammad and four other “militants” had been killed in a rocket attack by Pakistani troops.

Any suggestion that Mr. Muhammad was killed by the Americans, or with American assistance, he said, was “absolutely absurd.”

This article is adapted from “The Way of the Knife: The C.I.A., a Secret Army, and a War at the Ends of the Earth,” to be published by Penguin Press on Tuesday.