Javed Bhutto, a caregiver to mentally disabled adults, got home from work about 11 that morning with bags of groceries in his Toyota Corolla. After his overnight shift at a residential facility, he had stopped in a supermarket with a list from his wife. In the parking lot of the small condo complex where the couple lived, he stepped out of his car in the chill March air, opened the trunk and reached for his bundles.

A man identified by D.C. police as Hilman Jordan — who had killed before for no sane reason and was locked in psychiatric wards for 17 years — walked up behind Bhutto, pulling a 9mm semiautomatic from a pocket of his coat. Spreading his feet in a combat stance, he aimed the weapon with a two-handed grip at close range. Bhutto, leaning into the trunk, didn’t see him coming.

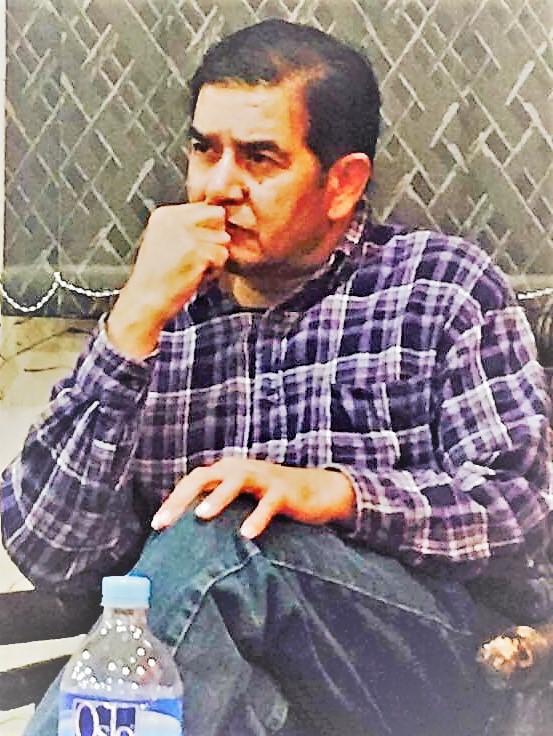

Although they were neighbors in City View Condos, in Southeast Washington, the two were barely acquainted. Bhutto, a few days shy of his 64th birthday, was a former philosophy professor in Pakistan who found a new career in his adoptive country, working in group homes. Jordan, 45, acquitted by reason of insanity in an unprovoked fatal shooting in 1998, had been released from St. Elizabeths Hospital and was renting a condo largely at taxpayer expense.

The first slug whizzed past Bhutto, striking the Toyota, and he spun around aghast, holding up his hands. The attacker tried to squeeze off another round, but the Smith & Wesson jammed. He racked the slide again and again, ejecting unspent cartridges onto the pavement, as Bhutto ran, arms flailing, toward the parking lot gate. The gunman caught him there, pistol-whipped him until he fell, kicked him twice in the head and fired a bullet into his heart.

Now the victim’s widow, Nafisa Hoodbhoy, 63, angrily wonders why the D.C. Department of Behavioral Health, legally obligated to monitor Jordan, wasn’t also required to warn City View residents that he was a St. Elizabeths outpatient with a homicidal history. And echoing others, she questions why Jordan was allowed to remain free despite what neighbors say was his chronic pot smoking — a trigger for his psychotic delusions and a violation of his court-approved release terms.

After Bhutto was shot to death March 1, detectives say, they saw Jordan sitting calmly on his balcony overlooking the crime scene, his right shoe stained with blood. They say they found a 9mm Smith & Wesson and a marijuana joint in the condo.

“Someone didn’t do their job, obviously,” Hoodbhoy, a journalist, says bitterly. “Someone who should have been watching this insane murderer didn’t do their job.”

Schizophrenia and paranoia had driven Jordan to kill years earlier. The court order authorizing his release from hospital confinement in 2015 required Behavioral Health staffers to screen his urine regularly for traces of intoxicants, and a failed test was supposed to land him back in St. Elizabeths immediately. Yet he rapped about pot use in YouTube videos that show him with apparent marijuana joints on his balcony, his eyes narrowing as he smokes. Neighbors say he would sit outside getting high for hours.

Seven weeks before the shooting, Bhutto, who lived directly above Jordan, complained to Jordan’s landlord about the persistent odor of marijuana coming from downstairs, and the landlord says he warned Jordan that Bhutto was upset.

After the killing, a prosecutor said in court, Jordan “tested positive for PCP,” or phencyclidine, a powerful hallucinogen. The drug, often mixed with marijuana, can induce frenzied aggression, especially in users who are prone to violence.

Jordan, about 5-foot-10 and heavyset with graying whiskers, also was forbidden to have a firearm; how he allegedly got one isn’t publicly known.

Citing privacy rules, the Behavioral Health agency, which pushed for Jordan’s release in 2015, won’t comment on his mental state then or discuss details of its supervision of him at the condo complex. The agency’s chief of staff, Phyllis Jones, says records show Jordan “was in compliance with the conditions of his discharge,” but she adds, “An internal review is ongoing.”

Today, six months after the shooting, the internal review still isn’t finished, Jones says.

D.C. Mayor Muriel E. Bowser’s office also won’t comment on Jordan, referring questions to mental-health authorities. In D.C. Superior Court, though, Judge Milton C. Lee Jr. made his opinion clear at a June hearing. Rather than return Jordan to St. Elizabeths, which is run by Behavioral Health, Lee ordered him jailed while he awaits a trial on a first-degree murder charge.

“I have no faith whatsoever” that the agency and hospital “will do what is necessary to keep you consistent with your treatment and to monitor you in a way that will protect the community,” the judge said, staring down at the shackled Jordan, who has yet to enter a plea in the killing. “It appears in this regard they have failed, and I’m not going to give them another opportunity.”

‘It’s just me — I did it.’

Born in 1973, Hilman Ray Jordan was raised in Silver Spring, Md., the second-youngest of eight siblings, according to a St. Elizabeths report. His stepfather was a custodian, and his mother stayed home with her children. “Mr. Jordan does not have a history of severe misconduct or any psychological disorder” as a child or adolescent, the report said.

His psychiatric treatment over the years is described in hundreds of pages of clinical documents filed in Superior Court.

After finishing high school, Jordan worked in landscaping and construction. In April 1998, he lost his maintenance job at a hotel. Struggling to get by, he moved back in with his mother and stepfather in their rented townhouse.

The onset of his psychoses that spring, weeks before his 25th birthday, was swift and devastating, a report said: He lost his appetite and 25 pounds; he showered 10 times a day; he became increasingly agitated and fearful — a recluse who hardly slept — thinking strangers planned to kill him; he “believed messages were being sent to him from the television”; he “heard voices in his head . . . being critical of him”; he pummeled a punching bag in the townhouse for hours at a stretch.

In an attempt to calm himself, reports said, he began smoking marijuana heavily that summer, which might have worsened matters. Studies show that the active ingredient in pot, known as delta-9-THC, can exacerbate the paranoia and delusions of someone in the throes of mental illness. As his downward spiral accelerated, a report said, “his family urged him to see a doctor, but he refused,” preferring to self-medicate with cannabis.

Then, in midsummer, he was gripped by an irrational belief that a relative and longtime friend, Kenneth Luke, had raped him. The imagined trauma and humiliation consumed Jordan’s disordered mind. “This man took my manhood,” he later told a homicide detective, “and I want it back.”

A little past 6:30 p.m. on Aug. 7, 1998, the two were walking in Southeast D.C. when Jordan pulled out a revolver, held it to his friend’s head and squeezed the trigger. Luke, 27, pitched to the pavement, mortally wounded. Jordan ran three blocks and waited on a street corner, gun in hand, until police cars rolled up. Surrendering without a struggle, he told the officers, “It’s just me — I did it.”

After being held in St. Elizabeths for months, taking a regimen of antipsychotic drugs, Jordan was indicted on a first-degree murder charge in January 1999. With his client locked in a hospital ward, awaiting a trial, lawyer Matthew Alpern argued to prosecutors that Jordan’s schizophrenia and paranoia had been so severe at the time of the killing that he wasn’t legally culpable.

Alpern said Jordan should be declared not guilty by reason of insanity and, like any insanity acquittee in the District, he should continue receiving treatment at St. Elizabeths until he was deemed safe enough to be released, as the law requires. The U.S. attorney’s office in Washington, which handles both federal and local criminal cases, waited to review more in-depth mental evaluations of Jordan before deciding how to proceed.

Here’s how the insanity defense works

Insanity-defense laws vary among U.S. jurisdictions. In D.C. Superior Court, as in about 20 states, a defendant is entitled to acquittal if he proves that during the offense, he “lacked substantial capacity to appreciate the wrongfulness of his conduct or to conform his conduct to the requirements of the law” because of mental illness.

Research shows that a majority of the public thinks the insanity defense is a loophole through which criminals often escape punishment. In fact, trials involving the defense are exceedingly rare nationwide, and the success rate for defendants in those cases is minuscule. Usually when lawyers invoke the defense, they have valid reasons for doing so, and prosecutors typically end up conceding that the defendants aren’t legally guilty.

So it was with Jordan.

Fourteen months after the killing, he admitted in court that he pulled the trigger, and a prosecutor acknowledged he wasn’t criminally responsible. On Oct. 1, 1999, a judge declared him not guilty by reason of insanity and committed him to St. Elizabeths.

Back then, the hospital, in Southeast D.C., resembled the 19th-century asylum it had once been, with Victorian-era brick edifices and acres of rolling fields behind a forbidding wrought iron fence. Today, the rebuilt hospital houses about 260 patients, half of them “civil commitments,” meaning people not charged with crimes. The rest, being treated in prisonlike wards, are insanity acquittees or defendants undergoing pretrial psychiatric evaluations or accused criminals found mentally incompetent for trials.

Jordan was ordered confined there “indefinitely.”

Which wouldn’t be forever.

‘Homicidal thoughts’

In the eyes of the justice system, he was innocent of any crime, and the hospital’s job was to reduce his psychotic symptoms until the law considered him fit to be released.

Jordan’s illnesses caused “persecutory delusions . . . hallucinations . . . and lethal conduct,” a clinical report said. But over time, psychotropic drugs led to “considerable improvement.” He learned coping skills and behavior-modification strategies. His marijuana dependence, a catalyst for his psychoses, was addressed in counseling. Gradually, his symptoms subsided, a report said, and he presented “little or no management problem.”

In December 2003, he would taste freedom again.

Just as the process of adjudicating insanity verdicts is highly subjective, so is the process of deciding when acquittees should be freed. Jurists and others without medical training are forced to predict the future behaviors of latently dangerous mental patients, relying on recommendations from psychiatrists who acknowledge that theirs is an inexact science.

If Jordan had been convicted of first-degree murder in 1998, he would have been imprisoned with no parole eligibility until 2028. But the legal principles for dealing with insanity acquittees are far different. The parameters were established by federal appellate decisions in the past half-century, including landmark U.S. Supreme Court rulings in forensic mental-health law.

People found not guilty by reason of insanity — known as NGRIs — can’t be punished. They are legally entitled to freedom after successful treatment, and hospitals must try to render them sane enough that they won’t pose too much of a threat if let out.

The ultimate goal for NGRIs is total liberty. But first comes a progression of smaller freedoms called “conditional release.” While still an inpatient, an NGRI might be allowed unescorted home visits a few times a year. If all goes well, these furloughs might be expanded to two visits a month or more.

In the District, the final phase of conditional release, before complete freedom, is called “convalescent leave” from St. Elizabeths, in which an acquittee resides in the community as an outpatient while being monitored by the Department of Behavioral Health.

The agency says 129 NGRIs are under its supervision. Of those, 61 are inpatients (about half of whom are occasionally let out of St. Elizabeths on furloughs). The remaining 68 are living full time in the community on convalescent leave — including 13 who, like Jordan, were charged with murder or manslaughter. The rest of the 68 were found not guilty by reason of insanity in assaults, arsons, robberies, burglaries, property crimes and “various sexual offenses,” the department says.

Every step in the incremental release process, each new liberty, requires permission from a Superior Court judge. In most cases, a defense attorney and a prosecutor negotiate the limits of a requested new freedom, with input from St. Elizabeths, and submit their agreement to a judge in the form of a proposed “consent order.” Before deciding whether to sign the order, the judge reviews a “risk assessment” prepared by the patient’s treatment team.

Here the process gets especially dicey.

As the D.C. Public Defender Service says in a manual for lawyers, “in order to grant conditional release, the court need not find that the acquittee’s release will pose absolutely no risk.” The standard is merely “preponderance of the evidence.” If the judge concludes there’s a 51 percent chance that the acquittee won’t be dangerous to the public, then the consent order must be approved — regardless of the 49 percent probability that the release will end badly, maybe tragically.

So it was with Jordan.

On Dec. 9, 2003, after a prosecutor and a defense lawyer negotiated the terms of Jordan’s first conditional release, Judge Fred B. Ugast signed a consent order allowing him to spend Christmas, New Year’s Day and Martin Luther King Jr. Day with his mother and stepfather in Silver Spring. In subsequent months, his furloughs were expanded until he was permitted to visit his family one day a week and every holiday.

It did not go well.

In 2005, Jordan was “feeling ‘stressed,’ ” which “led him to smoke marijuana,” prosecutor Colleen M. Kennedy said in a court filing years later. She said the U.S. attorney’s office didn’t know in 2005 that Jordan was violating his release terms. However, she said, members of his treatment team at St. Elizabeths were aware of several transgressions back then, which they failed to disclose to prosecutors or the judge.

“He submitted multiple urine screens that were positive for marijuana” and was “engaging in a sexual relationship with a female staff member,” Kennedy wrote. When Jordan’s mother reported that he tended to sit silently in her home, gazing into space, and that she felt nervous and ill-equipped to deal with him, the hospital staff assured her that her son was “fine,” Kennedy said.

Then, in June 2005, he stole a pistol from his stepfather during a home visit and smuggled the gun into St. Elizabeths, Kennedy wrote. Possibly because he had been using cannabis, he was having “homicidal thoughts” toward a fellow patient. Kennedy said Jordan “apparently made plans to shoot’” the man, “including requesting additional privileges to increase his chances of encountering the patient,” before he gave up on the idea.

“The gun was concealed on the hospital grounds for several weeks” in 2005 “while Mr. Jordan awaited an opportunity to confront the peer,” St. Elizabeths said in a court filing nearly a decade after the violation. Jordan told a counselor about the gun and his potentially deadly fixation in October 2005, a report said. Without informing the court or U.S. attorney’s office, the hospital terminated his furloughs and locked him in a maximum-security ward indefinitely.

Which, again, wouldn’t be forever.

Marc Dalton, chief clinical officer for the Department of Behavioral Health, says he and his staff are barred by law from commenting on specific cases. Asked about their confidence level in assessing patients such as Jordan for release, Dalton, a forensic psychiatrist, notes that recidivism among insanity acquittees is “very low.”

Still, he shakes his head.

“Even with the best treatment,” he says, “there are never certainties.”

‘Community re-entry’

After his admitted gun-smuggling in 2005, Jordan spent five years in maximum security and made halting progress in therapy, according to hospital reports.

Still plagued by “paranoid delusions,” he complained of “feeling snakes crawling on his chest and hearing hissing noises.” He “initiated” three fights with two patients, one of whom needed 17 stitches to close a mouth wound. In 2007, after he shoved a fellow insanity acquittee to the floor, fracturing the man’s collarbone, he “was observed to have more paranoid and delusional thoughts” and “worsened auditory hallucinations.”

In 2009, he told a counselor “that he intended to continue abusing marijuana when he was granted privileges,” a prosecutor said in a court filing.

His medications were adjusted, and his behavior slowly improved. He was transferred out of maximum security in 2010 and allowed to stroll the grassy acreage of St. Elizabeths. But that summer, after he again “disclosed homicidal ideation . . . regarding the patient he had planned to kill in 2005,” his grounds privileges were curtailed.

By 2012, though, upbeat reports were mentioning his “active and insightful participation” in counseling. He was taking Haldol, Abilify, Klonopin and Geodon, and a psychologist noted “the lowest baseline level of paranoia and anxiety” in Jordan that she had seen in four years. In a letter to a Superior Court judge, the hospital said he was ready for “a well-planned, gradual process of community re-entry.”

Thus the incremental steps of conditional release began anew.

His attorney at the time, J. Patrick Anthony, asked the court to let Jordan leave the hospital for unescorted weekend day visits with his family and for weekday therapy sessions at a community mental-health center. Prosecutor Colleen Kennedy, having just learned of his 2005 violations, “strongly” objected in writing, saying Jordan’s “own actions have clearly shown” that he “is not a good candidate for release.”

Kennedy wrote that she was “perplexed” by the proposed furloughs. However, she faced the fact that she would probably lose a court fight to keep Jordan confined, given the low legal threshold for an acquittee to gain release — the 51/49 percent “preponderance of the evidence” standard. So she and Anthony negotiated a consent order allowing for unsupervised trips to the community center but, initially, no family visits. In June 2013, Judge Lee F. Satterfield signed the order.

Anthony, Kennedy and other lawyers involved with Jordan over the years either won’t comment on him or didn’t respond to interview requests. A Superior Court spokeswoman says judges are barred by judicial rules from publicly commenting on defendants.

Sometimes, usually in notorious cases, the U.S. attorney’s office battles relentlessly to prevent releases, and judges seem more likely to err on the side of caution. After his insanity acquittal in 1982, for example, it took 34 years for would-be presidential assassin John W. Hinckley Jr. to get out of St. Elizabeths on convalescent leave, to live with his mother. But for acquittees who aren’t infamous, such as Jordan, the process often moves much quicker.

In 2013 and 2014, his furloughs were repeatedly expanded through consent orders until he was staying overnight with his family every Friday to Sunday.

Jordan’s treatment team enthusiastically supported his new freedoms. He was still hearing “a hissing sound which grows in intensity until he has the sensation of an electrical jolt emanating from his abdomen,” a report said, but the hallucination afflicted him mainly in the stressful confines of St. Elizabeths, not when he was out and about. In July 2015, the hospital joined Anthony in asking the court to let Jordan live in the community.

As an outpatient, he “should be monitored closely” for intoxicants, the hospital said, because “destabilizers such as marijuana” could cause a disastrous relapse. Otherwise, he “was found to be within the moderate range for risk of violent recidivism.” After the U.S. attorney’s office agreed to a consent order listing 19 conditions, including regular urine tests, Judge Satterfield approved Jordan’s convalescent leave.

All that remained was for the 42-year-old patient to find hospital-approved housing in the Washington area, with help from social workers.

They would not have to look far.

A sister’s murder

Javed Bhutto, born in 1955, was the eldest child in a Pakistani family of modest means. “For a while after college, his father sent him to medical school,” his widow, Nafisa Hoodbhoy, says. “But he didn’t like medicine. He preferred philosophy.”

Bhutto left his dusty hometown, 300 miles inland from the Arabian Sea, and traveled to Bulgaria, where he earned a graduate degree at Sophia University in the waning years of communist rule. In the late 1980s, back in Pakistan, he joined the philosophy faculty at the University of Sindh, eventually becoming chairman.

He met his future wife in tragic circumstances.

Hoodbhoy, a year younger than Bhutto, was raised in the sprawling port city of Karachi, where she attended English-language schools. After moving abroad in 1978, she got a master’s degree in U.S. history at Northeastern University and worked as a reporter for London’s Guardian newspaper. Then, in 1984, she returned to her male-dominated Muslim homeland to become a pioneering female journalist.

As the only female reporter on the staff of Dawn, Pakistan’s biggest English-language daily, her goal was to “affect change” for women in the Islamic world, many of them brimming with career aspirations, as she was, yet stifled and routinely victimized.

Fauzia Bhutto, a younger sister of Javed Bhutto’s, was killed in 1990 in Karachi at age 26. The death brought Hoodbhoy and Javed Bhutto in the same orbit. They formed a bond and later married.

So it was that in 1990, after a young medical intern vanished from her Karachi apartment and suspicion fell on her clandestine lover, Hoodbhoy was the first journalist to publicly identify the man: Rahim Baksh Jamali, a wealthy legislator and an influential member of the ruling Pakistan People’s Party. She also tracked down Jamali’s driver, who told her what he had told the police: that he was present when Jamali, middle-aged and married, shot his mistress in her bedroom, and that he helped Jamali get rid of her body.

The intern, Fauzia Bhutto, 26, turned up dead on remote scrubland. As the case became a cause celebre, with women’s groups clamoring for Jamali to be punished, the victim’s brother Javed Bhutto was a beacon of calm and resolve. The philosophy professor, the eldest surviving male in his family, was duty-bound to seek redress. And he meant to do it his way — not violently or by tribal custom, but through Pakistan’s judiciary, which he believed should function blindly for both sexes and without favor to the politically connected.

Bhutto “knew full well that the administration would not act unless pressured,” Hoodbhoy wrote. For weeks in 1990, as he gently, doggedly implored legal authorities to do their jobs, Hoodbhoy studied him with a reporter’s eye — this “unselfconscious” fellow “driven by a sense of purpose” — and she watched admiringly as the women’s protest movement coalesced around him. “The victim’s brother mobilized society to follow the rule of law,” she told readers.

Jamali, who was arrested and jailed for two years before getting out on bail, lost his seat in a provincial assembly. But his trial dragged on for more than a decade until the driver recanted his story and Jamali, now deceased, was acquitted by a judge.

As for Hoodbhoy and Bhutto — “a study in contrasts,” the pushy newshound and the reflective scholar — they formed a bond that ran far deeper than their common interest in civic integrity. On Aug. 28, 1992, they married.

“He was my everything,” she says now.

A new country, a new life

After a tumultuous decade of democracy, Pakistan’s return to military rule in 1999 prompted the couple to emigrate.

They moved into a tiny apartment in Massachusetts — just the two of them; they never would have children — and Hoodbhoy began a teaching fellowship at Amherst College in 2001. Bhutto thought he’d find a place in academia, too, but it turned out his Soviet-bloc master’s degree and Pakistani professorship weren’t sufficient for U.S. higher education.

He toiled in low-wage jobs for months before discovering a new vocation, working in group homes with developmentally disabled adults. “He had such a way with people, such compassion,” his widow says. “Even the mentally effected people really took to him. I mean, he adored them.”

In 2003, Hoodbhoy joined Voice of America in Washington as an Urdu-language radio host. (She now writes for VOA’s Extremism Watch Desk.) She and Bhutto bought a one-bedroom unit at City View Condos, a brick blockhouse in the tumbledown Barry Farm area of Southeast D.C. Hoodbhoy planted peppers and cilantro in balcony pots, and Bhutto stuffed the place with his vast collection of philosophy texts. In 2012, they raised their right hands in a federal building and were sworn in as U.S. citizens.

A Northern Virginia nonprofit, CRi, which says its mission is to help people with developmental disabilities improve their lives, hired Bhutto in 2015 as a caregiver in an Alexandria group home — and he would work there happily until the morning he was killed. “He was so adept at knowing what everyone’s needs were,” a former colleague says, referring to the support Bhutto gave to the home’s four residents. “He’d study them, study their cues, and understand them as unique human beings.”

In his adoptive country, he went by the first name “Jawaid,” which is pronounced in English the way “Javed” sounds in Urdu. Hoodbhoy recalls hearing him in the condo bedroom holding forth in their native language on Skype and Facebook Live. Scores of students at his old university would gather for video talks by the long-departed professor, who lectured for the joy of it.

She’d peek in, see him hunched at a computer under shelves filled with books, smiling, gesturing, querying, expounding.

“Content, at peace,” is how she remembers him.

‘Not crazy’

Newly approved for convalescent leave, Hilman Jordan moved into a rental unit at City View Condos, a mile from St. Elizabeths, on Dec. 3, 2015, taking up residence directly below Bhutto and Hoodbhoy in the three-story building.

The unit’s landlord, Joe Holston, a friend of Jordan’s, says he heard from mutual acquaintances that Jordan needed a place to live. The two had known each other since boyhood, and Holston, now 42, had occasionally visited Jordan in the hospital. He says Jordan “always seemed okay to me in there. You know, not crazy.”

Leasing his condo to Jordan was a safe deal for Holston because the Department of Behavioral Health gives city housing vouchers to insanity acquittees on convalescent leave. Jordan’s share of the $1,200 monthly rent amounted to 30 percent of his Social Security disability benefit, while the D.C. government took care of the rest.

At Behavioral Health, the forensic outpatient department was responsible for making sure Jordan obeyed his release terms, which mandated frequent therapy sessions and check-ins with a counselor, who was supposed to visit him in the condo at least once a week. His meds, switched from oral to longer-acting injections, were to be administered by mental-health workers on a specified schedule.

Jordan was required to appear regularly at the outpatient department’s Northeast Washington offices, not only to get his injections but also to have his urine tested at least once a month for traces of intoxicants.

City View’s other residents were left in the dark about his history. “There is no legal reporting requirement to notify neighbors that an NGRI is living within the community,” a spokeswoman for Behavioral Health says. Holston, who resigned as president of the City View owners association after the killing, says he also kept quiet about Jordan, telling no one in the building that his tenant was fresh out of St. Elizabeths, having shot a friend in the head in the throes of a psychotic delusion.

No law required Holston to warn people. Asked why he didn’t alert them, anyway, he says, “I don’t know.”

‘They call me dynamite’

In Jordan’s time at City View, a span of 39 months, Behavioral Health staffers had nothing negative to say about him in three brief reports on file in Superior Court.

After his release, Jordan got married. He attended Narcotics Anonymous conventions in Ocean City, in 2017 and 2018, and in August 2018, he and his wife celebrated their wedding anniversary in Williamsburg, Va. In notifying the court and U.S. attorney’s office that Jordan planned to take the trips, different mental-health workers used identical language in the three reports.

“He visits the Forensic Outpatient Department (FOPD) every month for psychiatric management and monitoring of compliance,” was all they said about his conduct.

At the condo building, Joyce Morris, a tenant who befriended Jordan, says Jordan’s wife sometimes angrily moved out, leaving him by himself for long periods. “Smoking marijuana, it was like his everyday relaxing thing,

chilling on his balcony,” Morris recalls. “That was his zone, you know? His peace zone. Hanging on his balcony, smoking his weed. He’d be there for hours and hours.”

Morris, 53, lives on the first floor, which is partly below ground. The second floor, where Jordan lived, is near street level. She’d sit on the building’s front stoop, with Jordan just to her left, perched on his balcony, and “we’d talk about our issues,” she says. “Me, I’m bipolar with a little bit of schiz, and I’d be like: ‘Why I can’t be normal? Why I can’t have a life without all these meds?’ And him, too; that’s the way he was — like his problems had him down to where he didn’t care what happened.”

Gazing at her lap in the dim light from her kitchen, she says quietly: “He was a beautiful man, a beautiful man with a mental illness. And his mental illness got the best of him.”

Last summer, when Jordan’s marijuana habit grew “really heavy,” Morris says, she wondered about his drug tests. In some cases, delta-9-THC, the mind-altering chemical in cannabis, can be detected in the bodily waste of a frequent user even after 60 days of abstinence. Yet there was Jordan, week after week, getting high on his balcony, Morris says. Although she never asked him about it, she says, “the way he was smoking, I didn’t figure he had to take them urines anymore.”

On the balcony directly above, where Hoodbhoy nurtured her garden in the warm weather and her husband liked to sit and read, the reefer aroma became too much for Bhutto. One day in June 2018, he asked his wife, “What do you think I should do?” Hoodbhoy, who has a weak sense of smell, suggested he try to ignore it.

The couple knew little about Jordan, just that he was an odd-looking sentinel peering out from his balcony at the small parking lot. They’d smile and nod hello, and he’d nod and smile back. “Javed said he reminded him of the mentally effected people he attended to in his facility,” Hoodbhoy says. “We thought, well, he’s probably being put here by some kind of social worker or institution and they’re taking care of him.”

In the fall, after they closed their balcony door for the season, the odor of marijuana came up through the floor inside, further annoying Bhutto. Downstairs, meanwhile, Jordan recorded video rap-rants posted to his YouTube account in November, featuring bitter, frenetic, semi-coherent laments about his 17 years of hospital confinement.

In one, after taking a drag of what appears to be a joint, he squints. “They cause psychotic disorder/they said I smoke too much.” Waving a hand, he gives a shout-out, “Hey, ’OPD,” apparently meaning Behavioral Health’s forensic outpatient department, known in the court system by its initials. In another, there’s a close-up of rolling papers and an apparent joint on his balcony table, followed by a panning shot of the parking lot, soon to be a homicide scene. “Don’t get too close/they call me dynamite/and nothin’ can save you.”

Finally, on the evening of Jan. 17, Bhutto emailed Joe Holston, Jordan’s landlord, complaining about the pungent aroma permeating his and his wife’s condo. “Our clothes, bedsheets. . . . Other people visiting this building has also observed that it smells as if someone is smoking ‘weeds’ here.”

“I will look into this issue,” Holston replied the next morning. “Sorry for any inconvenience.”

He says he warned Jordan that the neighbors right above him were griping about his pot smoking, and Jordan agreed to stop. “He didn’t seem to think it was an unreasonable request,” Holston recalls. Hoodbhoy says the odor went away for a while, but in February, a few weeks before the shooting, it came back strong. And Jordan’s demeanor toward her and Bhutto turned cold.

They’d nod hello, she says, and he’d stare.

The morning it happened, March 1, she was at work.

From a security camera:

Bhutto, done with his overnight shift, pulls into the lot in his Toyota at 10:56 a.m. and parks in spot No. 7, directly below his and Jordan’s balconies. On the second floor, a man identified by police as Jordan leaves the balcony and walks downstairs to the lot. He is smoking something.

Bhutto opens the trunk and bends in, gathering his groceries. The attacker strides toward him, a hand in a pocket of his coat. Whatever he’s smoking, he flicks it away.

“I won’t watch,” Hoodbhoy says of the video. “I can’t.”

A week later, she flew to Pakistan to bury her husband in Shikarpur, his hometown, next to the grave of Fauzia Bhutto, dead almost 30 years. The crowd that gathered at Karachi’s airport for the coffin’s arrival — relatives and friends, former colleagues, old philosophy students and comrades from the women’s protest movement — overwhelmed Hoodbhoy, who led a caravan of mourners inland for the interment.

A slain sister, a slain brother, side-by-side now in the provincial dust. For Fauzia, there was no justice. For Javed, she can only hope.

paul.duggan@washpost.com