I first met Benazir Bhutto in 1986 at the Karachi Press Club (KPC) – where she had come to meet members of the press. A bevy of journalists surrounded her, as she was taken to the upper floor of the building. The former president of KPC, the late Mahmood Ali Asad thrust me through the crowd to introduce me as the “active lady reporter from Dawn”. Poised and dignified – a white silk dupatta around her hair – Benazir smiled graciously and made room next to her with the words:

“Oh, I thought you were a school girl.”

I was seated next to her and I worked to take advantage of it. I asked Benazir if she would give me an interview for Dawn on the Islamic fundamentalist laws relating to women. The Zina Ordinances had by then forced women to disappear from public spaces. As a woman who campaigned for the public post of prime minister, Benazir’s position on the Islamist laws had not been publicized and I hoped to be able to do just that.

Benazir looked hard at me, indicating that she was weighing up the benefit of giving me an interview that would strike against the ruling Gen. Zia. In characteristic fashion, she threw me a counter question: “Can you write a paper detailing the laws that have been passed under Gen. Zia and their implications for women?”

The counter-offer took me by surprise. And yet, living with the effects of the discriminatory laws every day, I was happy to further her understanding of them. We parted with a common understanding that I would write a paper on the situation and she would give me an exclusive interview on the subject.

For the next several weeks I researched the Islamist laws at a little library in Karachi, set up by an academically-oriented women’s organization called Shirkat Gah. It was the forerunner to the activist Women’s Action Forum and War Against Rape – civil society organizations from a privileged class, which took enormous risks to protect the most vulnerable sections of society.

I had the document delivered to Benazir, and received word through her party members that it was a “well researched piece.” Still, three months went by and there was no word from the woman who went on to become prime minister.

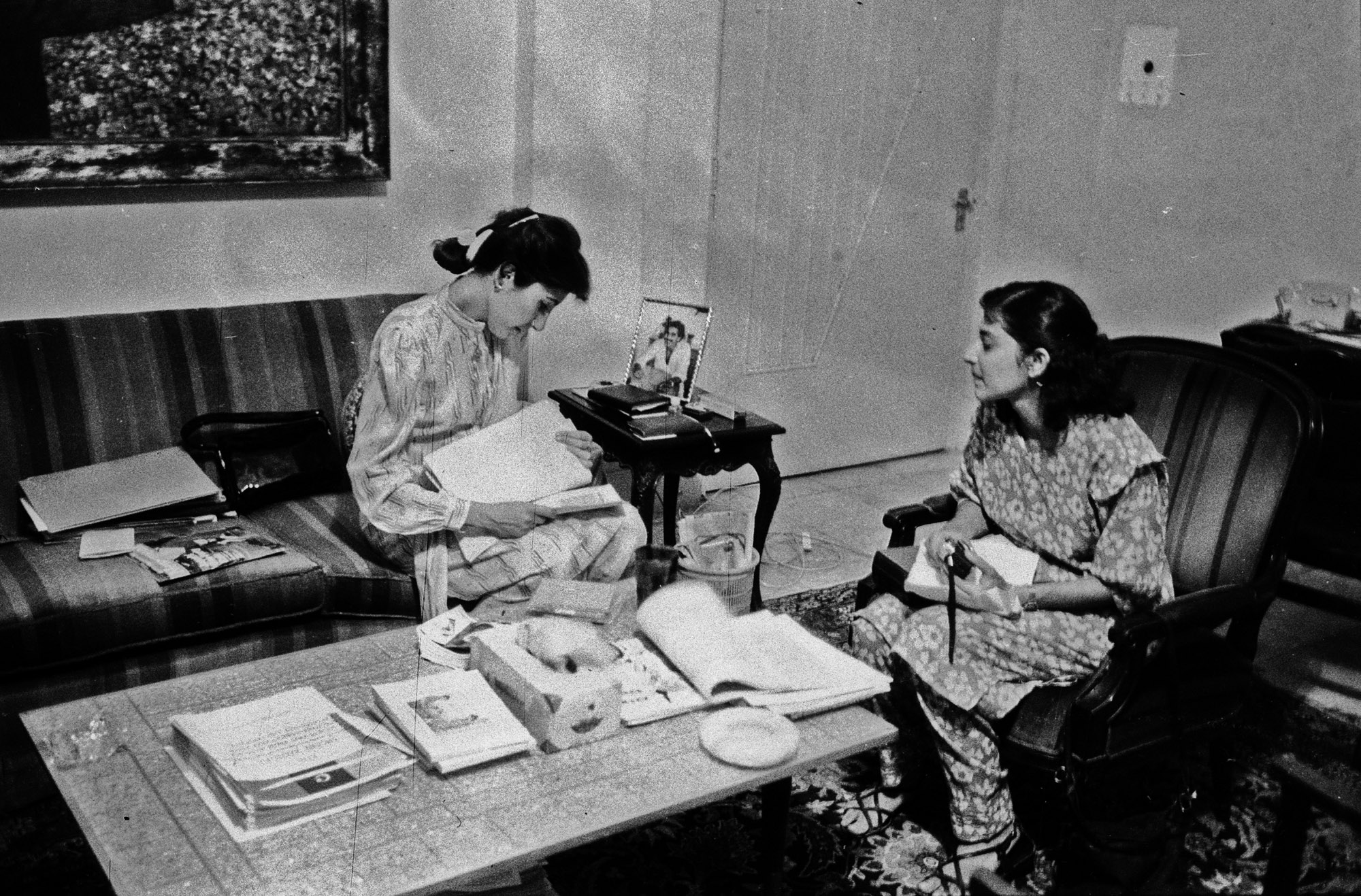

Finally, out of the blue I got a phone call from 70 Clifton, Benazir’s ancestral mansion in Karachi, saying that she wanted to see me. Armed with a tape recorder, I sped to her residence, ready to interview her. To my surprise a handful of women activists were already there. Benazir had invited them to consult whether she should give me the interview.

It was 1986 and Benazir was still unmarried. That was apparently the stumbling block for the 33-year-old woman, who – notwithstanding her Western education – had roots in Larkana’s feudal culture. “What will the Mullahs think about me, a single woman…talking about issues such as rape?” she quizzed us frankly.

I was perplexed. As privileged women we knew that the Islamist laws were implemented in the harshest possible way on poor women. But I wondered if Benazir had thought about the irony of becoming the prime minister of a country where discriminatory laws would still treat her as a second-class citizen.

The Western-educated women – mostly from the Women’s Action Forum – had long waited for the opportunity to turn around the situation for women. Knowing that Benazir stood a good chance of becoming Pakistan’s first woman prime minister, they convinced her that the time was right for her to pledge her support for women’s rights.

Apparently our presence prevailed on Benazir. The next day, I got an urgent message from 70 Clifton that Benazir wanted to see me right away. Once again, I sped in my purple soap-shaped car to her ancestral home. Benazir didn’t need to be asked any questions. Instead, in an unstoppable monologue, she regurgitated the points I had provided in my paper.

On July 11, 1986, Dawn published my 45-minute interview with the headline, “Benazir Decries laws and Attitudes that Degrade Women.” Benazir had praised her late father, Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto for his role in the advancement of women’s rights. Most importantly, she made a commitment that if elected as prime minister she would repeal the laws passed by Gen. Zia ul Haq.

The PPP-led government is facing a crisis that erupted after its junior coalition partner, the Muttahida Qaumi Movement (MQM). Mr Taseer had said it would survive.