MOHAMMAD AGHA, Afghanistan Oct 12 — Greg Mortenson is hurtling down the dusty back roads of eastern Afghanistan, hoping the Taliban won’t attack his Toyota 4Runner. There are no police checkpoints, no American troops and no sign of any foreign development projects — including his own.

MOHAMMAD AGHA, Afghanistan Oct 12 — Greg Mortenson is hurtling down the dusty back roads of eastern Afghanistan, hoping the Taliban won’t attack his Toyota 4Runner. There are no police checkpoints, no American troops and no sign of any foreign development projects — including his own.

A few years ago, when the author of “Three Cups of Tea” was one of the world’s most beloved activists, there would have been a host of American officials waiting for him. But now, with his reputation in a shambles, he has slipped back into Afghanistan quietly.

When he arrives at an unmarked blue gate in a mud wall, his driver stops. Inside, Mortenson says, lies “the other side of the story” — hundreds of Afghan girls getting an education, thanks to him.

Except no one is answering the door. The place looks abandoned.

“Maybe everyone is at a wedding,” he says with a forced laugh. He squirms in his seat.

Mortenson won fame as a humanitarian who built hundreds of schools in Afghanistan. Four-star U.S. generals sought his advice on Afghan tribal dynamics. President Obama donated $100,000 of his Nobel Prize winnings to Mortenson’s charity. Former president Bill Clinton praised him. Four million people bought his book.

Many of his former advocates now see him as a fraud.

A 2012 investigation into his charity, the Central Asia Institute, found that he spent millions in donations on his expenses, including travel and clothing. His book turned out to contain large-scale fabrications. Some of the schools he boasted of had no students. Some appeared not to have been built at all.

Now, Mortenson is trying to start over, to emerge from years of pain and disgrace. His donations have crashed. His co-author committed suicide by kneeling in front of a train. His daughter tried to take her life. He almost died of heart failure.

Mortenson, 56, is wearing Afghan clothing — a flowing tunic and flat wool cap. He sits in the truck on this sunny morning, staring at the blue gate, which remains closed. He is tapping his foot. The minutes pass slowly.

Then the gate opens.

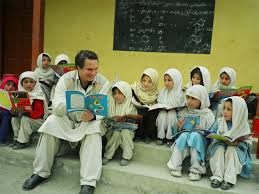

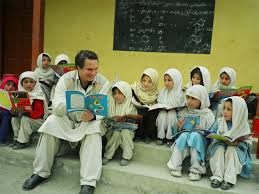

The girls are everywhere, skittering near the front steps of the school, in blue uniforms and white headscarves. Mortenson’s face lights up. He bounds from the SUV and embraces the male teachers, putting his hand on their hearts, a sign of respect here. He shakes the hands of the little girls.

“This is where I belong,” he says.

Return to public life

In Afghanistan, Mortenson is still “Mr. Greg,” the man who can transform a village of illiterate farmers by writing a check. Word of his disgrace barely arrived here.

He has come back to Afghanistan several times since his fall from grace, quietly visiting schools. But on a trip this summer, he invited a reporter to spend a few days with him. It was a first step in Mortenson’s return to public life — one he hardly seems ready for.

He is a man who struggles to find the right words. Back when he was appearing on TV and giving speeches, he had to train himself to project confidence, to memorize snappy one-liners about girls’ education.

Today, Mortenson prefers to regard his celebrity as an accident.

“Americans want heroes to believe in. Once the machine kicks in, you can be pretty much anyone, and people will flock to you,” Mortenson had said as his truck bounced along the 20-mile road between Kabul and the girls’ school, in Logar province.

Still, he had embraced his fame. He had long been a misfit: a white kid in Tanzania, the son of Lutheran missionaries, then a teenager who got beaten up when the family returned to Minnesota and he identified himself as African. Then, he was a traveling nurse in South Dakota and Indianapolis who struggled to put down roots.

He aspired to do great work but was never the best at anything. Then, suddenly, the world was praising him as the man deified in “Three Cups of Tea,” a book carefully, even deceptively, crafted to make Mortenson look heroic.

For an America at war in faraway Afghanistan, he had at least some credibility. He had traveled for years in Pakistan and Afghanistan, and built his first school in rural Pakistan in 1996. When the book came out a decade later, his insights were marketable.

For U.S. generals trying to apply counterinsurgency theory, he shuttled tribal elders from remote villages to Kabul. For suburban American book clubs, he explained: “War will ultimately be won with books, not with bombs.” The phrase didn’t even resonate with him — he knew of plenty of hardened militants who would never allow a secular school in their village — but it somehow seemed to with everyone else.

Donations shot to nearly $23 million in 2010. And then came the downfall. In 2011, the television show “60 Minutes” said the book was largely fabricated and that he was taking money from his charity.

Jon Krakauer, whose e-book “Three Cups of Deceit” remains the most authoritative account of Mortenson’s misdeeds, accused him of lying about practically everything — “the noble deeds he has done, the risks he has taken, the people he has met, the number of schools he has built.”

Recounting his mistakes

Three years later, sitting in the garden of his run-down Kabul hotel, Mortenson admits some mistakes. Take his account in “Three Cups of Tea” of how he found his cause. An amateur mountaineer, he was descending Pakistan’s famed K2 peak in 1993. He was weak and delirious, the book recounts, when he stumbled into a village called Korphe. The book describes how the locals took him in and how he developed a “routine” in the village, where he was deeply moved by the poverty.

Now, Mortenson says, he was only in Korphe for a few hours. His relationships with the villagers, he says, developed in subsequent visits.

“It was obviously a lie,” he said. “I stand by the story, but there were compressions and omissions.”

He said that he didn’t pay close attention to the writing of the book, thinking of it mostly as a vehicle for raising awareness and donations. The book was largely penned by his co-author, David Oliver Relin.

Then there is the question of how many schools Mortenson built. When he was asked for statistics, he says, he would sometimes guess.

“It was misleading,” he said.

In truth, even the U.S. military has difficulty keeping track of how many of the schools it built are still operating. Sometimes, Mortenson just says what he thinks will make people happy — at least that’s what his therapist told him.

Mortenson acknowledges that the Central Asia Institute (CAI), which he founded in 1996, kept poor records.

“Myopic passion,” his wife, Tara Bishop, called it — explaining how her husband’s devotion to his cause outstripped his management abilities.

For all his admissions, Mortenson hasn’t given up on the image of himself as an altruist. After meeting a reporter, he began forwarding old e-mails from Hollywood figures.

“I very much enjoyed our meeting and look forward to following your travels,” actor Brad Pitt wrote in 2010.

“You have already turned the daunting and the impossible into reality,” a film producer wrote in 2008.

“I turned all film offers down, even when the offers went high,” Mortenson said in an e-mail.

Financial issues revealed

The biggest indictment of Mortenson is his financial mismanagement — specifically his use of CAI donations to fund speaking tours in which he promoted “Three Cups” and a sequel, “Stones into Schools.” Mortenson was paid tens of thousands of dollars per speech in addition to receiving royalties from book sales. In many cases, he even charged his charity for expenses covered by other sponsors.

In 2012, the attorney general’s office in Montana, where he lives, ordered him to return more than $1 million to the charity, which he paid from his book profits. He was forced to step down as a voting member of CAI’s board of directors. Mortenson is still a senior staff member, earning more than $150,000 a year.

But even now, trying to calculate his income and the amount he donated to CAI over the years, Mortenson gets lost in a series of incomprehensible Excel spreadsheets. Trying to explain them to a reporter, he attempts to do the arithmetic, gets it wrong and starts all over.

“I suck as an administrator,” he said. “The book was the best thing we had. By promoting the book, I was bringing in money to CAI.”

There is an alternative explanation. For years, employees of the charity had badgered him to document his expenses and improve management practices. “He resisted and/or ignored them,” the attorney general’s report said.

Krakauer, writing recently for Medium.com, described Mortenson as a natural con artist.

“Mortenson’s success at dodging accountability can be explained in part by the humble, shambling Gandhi-like persona he’s manufactured for public consumption,” he wrote.

Success despite scandal

Yet Mortenson can’t just be dismissed as a greedy opportunist. He still takes considerable risks to see his schools. Because of security threats, many foreign aid workers based in Kabul rarely visit their projects.

Despite all of his mistakes, CAI is still one of the largest education nonprofits in South and Central Asia, with thousands of children attending his schools, most of them girls. That’s partly due to the amount of money Mortenson was able to raise. But his charity also managed to forge unusually strong bonds with the rural communities where he built schools.

Ahmed Rashid, a well-known Pakistani journalist and expert on the Taliban, recalled his shock at meeting Mortenson. “He has odd socks on and odd shoes on. He’s not a smooth guy,” he said in an interview.

But the more Rashid spoke to Mortenson, the more the journalist was impressed with the American’s knowledge of local tribes.

“He’ll come out of a village and tell you who is al-Qaeda, who is Northern Alliance, who is pro-government,” Rashid said.

It is true that some of Mortenson’s promised schools aren’t functioning. Last year, a Washington Post reporter trekked across the Wakhan Corridor in northeastern Afghanistan, where many of the charity’s schools were built. Several of them were vacant. In one, the desks and chairs were in a pile. Many of CAI’s schools were clearly built in the wrong places — away from population centers.

But nearly every aid organization here has had failures. In some cases, foreign donors constructed schools and handed them to the government to run; they weren’t maintained. U.S. military units often built schools that closed as soon as those troops withdrew from the area.

At Mortenson’s school in Logar, every classroom was full. In one, he pointed to a girl wearing a black headscarf.

“Her father is a Taliban commander,” he whispered to a reporter. “When she came to the school, other families felt it was safe to send their daughters, too.”

It was not possible to confirm such deals. But the Taliban had shuttered nearby schools, deeming their curricula “un-Islamic.”

In the school, Mortenson was a man transformed. He went room to room, teaching arithmetic with a handful of stones. Suddenly, the inarticulate man was funny and no longer self-conscious. He made eye contact with every student.

CAI has $20 million in reserves, but donations have dried up. According to its financial report, it raised about $3 million last year but spent more than $5 million. As he watches the funds dwindle, Mortenson feels guilty and angry.

“I just don’t understand why all these people are trying to bring me down instead of help me,” he said.

‘Almost broke’

In June, nearly as soon as Mortenson arrived in Kabul, the cellphone of the CAI employee who handles his communications started ringing nonstop. Men in Nuristan province wanted a new school. A group in Nangarhar province wanted higher salaries for teachers.

The Nuristani group, long-bearded men from a war-torn province, met him at Kabul’s Intercontinental Hotel, home to a restaurant with white tablecloths and waiters in suits. In the lobby, Mortenson grew nervous, mumbling to himself — not only could he not promise them a school, but he worried about the cost of their dinner.

The Montana attorney general is keeping a close watch on CAI’s expenditures these days. Mortenson says legal costs and the attorney general’s fine have left him “almost broke.”

“It’s probably very expensive,” he said in the hotel lobby.

Mortenson might not be the foremost expert on Afghan culture, but he knew that it would be inappropriate to turn away a group of visitors. When the bill came, he picked it up. It was about $250. He told the men he would try his best to build the school, even though he knew it was out of his hands.

“Before everything happened, I could have done more,” he said later. “There hasn’t been a school in Nuristan for years.”

Uncertain future

At its height, CAI’s Kabul office was buzzing with employees. These days, it’s nearly empty. The employees are mostly cataloguing financial records — cabinets full of paper receipts and handwritten attendance records, which Mortenson points to with pride.

He is hoping his organization can stay afloat; its board has been pushing him to resume public appearances, to jump-start fundraising. But its future is as uncertain as his own.

When he’s at his home in Bozeman, Mont., he spends much of his time reading about Afghanistan and Pakistan on the Internet, and posting links on Facebook.

But he also daydreams about leaving his charity behind. He could spend more time with his wife and children: Khyber, 12, named after the Khyber Pass, and Amira, 18, which means “female leader” in Persian.

Amid all the pain of recent years — his co-author’s suicide after the public disgrace, his near heart failure, which confined him to bed for months — his biggest regret is how he neglected his children during the years of his soaring celebrity. His daughter’s suicide attempt drove that home.

“I’d just been out of the picture. I feel terrible about that,” he said, his voice wavering in a rare display of emotion.

Now, he is weighing his options. He could try to return to public life, to write another book or advise those looking to start nonprofits. But he often seems unready to reemerge.

“Sometimes, I think it would be better if I just stopped talking,” he said. “This stuff from the past is going to come for a long time, whether I say everything was or wasn’t a lie.”

During one of his classroom visits in Kabul, he walked from desk to desk, asking 9-year-old girls what they planned to do when they got older. Some wanted to be midwives or doctors. Others wanted to be teachers. As he saw it, their ambition was another validation, another sign that he shouldn’t give up.

He came to the desk of a girl with a wide smile.

“I want to be a lawyer.”

Mortenson shook her hand.

“I could use some more of those.”

He has, at least, made one concrete plan for his own future. Next year, he’ll enroll in graduate school courses on organizational leadership.

“I’d really like to understand what it is to really be an ethical leader,” he said.