Islamabad, March 8 – Challenging male dominated politics in Jhang was not an easy step. Taking a lead role in a conservative Afghan society was not a bed of roses. Speaking against female genital mutilation was no simple task. Branding women’s transformed role through advertisements was not a welcome step. Putting women in active political roles in Sri Lanka was not entirely rewarding. Using music for social causes wasn’t a sweet song either.

Six women – from Pakistan, India, Afghanistan, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh and the US – shared their success stories, fraught with challenges but also with achievements, with a 300-strong audience at the International Women’s Empowerment Conference-15 in Islamabad on March 6 as part of Women’s Day celebrations.

As the panelists took turns, it emerged women’s oppression keep on changing its form with the change of places; the only thing that remained permanent was some women’s resilience and courage to fight back.

The panelists included former ambassador and minister Syeda Abida Husain, Scroll.in journalist from India Aarefa Johari, lecturer Tania Aria from Kabul University, attorney-in-law in Colombo Selyna Peiris, Sara Ali a businesswoman from Bangladesh and musician-cum-social activist from US Mary McBride.

Abida Husain started off her political career as a Member of the Provincial Assembly (MPA) in the 1970s. After Ziaul Haq’s martial law, she took part in local council polls and was elected ‘chairman’ of the Jhang District Council.

“Some people asked me to use ‘chairperson’ instead of ‘chairman’ and I told them that let me chair the men, not persons,” Abida said.

During her political career, she launched several development projects such as farm-to-market roads, schools and health facilities in rural areas, which ultimately brought about development and empowerment for women. But the more obvious and clear mark her politics left was a woman’s courage to come out for equal rights in a male-dominated society.

Aarefa Johari has taken it upon herself to raise awareness against female genital mutilation (FGM), a common, ancient and religious practice among her Dawoodi Bohra community in India and elsewhere.

In the community, every seven-year-old girl has borne this ritual, called khatna or circumcision. She said that like other girls, she had to undergo this ritual. With the passage of time, the pain and memory of the horrendous surgery faded, Aarefa said, adding that education helped her realise that the future generation must not go through the painful experience. She says women from her community have a strong belief that religion allows FGM which suppresses women’s sexual pleasure.

Aarefa says strangely most men are unaware of the practice as only clerics and women have carried the practice forward “to save their virtue”. She said the frustrating thing was that clerics have chosen not to respond to facts, which she says she and other people have started debating.

“The satisfactory part is that I’ve stirred a debate and people are listening to me, though in disbelief,” Aarefa said.

Selyna Peiris says she believes in women’s economic independence. She runs handlooms where 1,000 women are employed. She says she belonged to a privileged Sri Lankan family and at the age of 16 flew to Britain and returned after receiving a law degree.

After launching and succeeding in handloom products, Selyna decided to go and ask women what they needed.

“As the country was passing through a post-war era, I decided to take civic liberty causes and set up a legal aid centre for women,” she said.

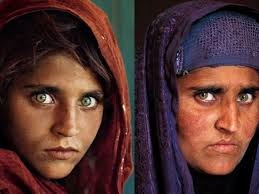

Unlike Selyna, Tania Alia has seen displacement and migration from Afghanistan to Pakistan, the Taliban’s anti-women regime and education in schools which lacked in facilities from chairs to drinking water. Tania said she was only two when her parents decided to leave Afghanistan for Pakistan and returned to Kabul 13 years later. She remembers when she was traveling with her mother in a bus and a Taliban squad pulled in.

“A Taliban militant started beating a woman for not wearing her burqa properly,” said Tania.

Time went by, the Taliban regime fell and the new government took over. She said the initial days were hard when her family home had electricity for five hours a day after every two days. Tania attended university and completed her graduation after which she was offered a job as a lecturer at the same institution. With her ceaseless struggle, Tania has secured scholarships of prestige and has worked with Trade Accession and Facilitation for Afghanistan (USAID), International Relief Development (USAID) and Public Finance Management Reforms (World Bank). Her journey goes on.

Sara Ali, a Bengali businesswoman from the advertisement industry, went for social activism when she married a man who was not of her religion. After breaking the taboo, she decided to launch awareness among women to understand the issues of their own daughters.

Sara used social media as a tool to reach millions of women. “Female contraceptive was an untouchable subject, but not anymore,” she said, explaining how she used social media to help women improve their health through birth control.

Mary McBride, unlike most singers, talks at social fora and writes songs that incorporate social themes. Her band is on international tours most of the time during which she uses music to highlight issues confronting women.

Six women, six stories — but that is not the limit. Every woman has a story, of successes and failures, narrating a journey that documents her struggle to claim her space in a society which may have had little to offer her in the first place.